Modern folk beliefs V: “Your ancestors had kids in their teens”

How marriage and family structure really differed across the world in history

This article is the fifth in a series on modern folk beliefs. In the series so far:

“Your ancestors had kids in their teens”

At various points over the years I’ve observed people in Britain and the West in general failing to grasp how much marriage and family structure varied across the world throughout history. These misunderstandings are seldom stated explicitly, and likely not held fully consciously, but you can detect it via throwaway comments. “Girls used to be married off and have kids in their teens” is one example. References to “the Taliban’s medieval attitude to women” is another, or “they are 500 years behind”. Or in response to some way women are oppressed somewhere else in the world, “what about how women were treated here in the Victorian era?”

If I were to make this view of history more explicit it would be something like:

People everywhere used to live in a uniform, static, and gender unequal ‘traditional past’, but modernity has and will continue to transform these societies in the direction of freedom and gender egalitarianism.

This viewpoint does describe a real trend – clearly, gender relations and family structure have been transformed globally over the last few hundred years. Most places in the world are more liberal and gender egalitarian today than they were in 1800, and on the whole there is a correlation between these changes and being more politically and economically modern. However, the broad trend leads people to miss the immense variation that existed historically across the world before the global transformation began.

This article will go into these differences in more depth, and will investigate the origins of the misconceptions. First I’ll provide a brief overview of the differences here, to be expanded on in the next section. The age at which girls married ranged from early teens in India, mid teens in the Arab world, late teens in China, to mid twenties in parts of northwestern Europe. Choice of marriage partner was to a significant extent up to the couple in northwestern Europe, but arranged elsewhere, ideally with a first cousin in the Muslim world or South India, but with non-kin elsewhere in India and in China. Once married the couple might live in a newly established nuclear household in parts of northwestern Europe, with the husband’s parents in China, or in a joint extended family household in India. Lines of descent among the nobility were traced both through the male and female lines in Europe, but only through the male one in much of the rest of the world. Aristocratic women might live their lives secluded from unrelated men in the Muslim world and India, or socialise in mixed-sex environments as in European courts.

The previous modern folk beliefs that I’ve written about had quite clear and recent intellectual origins, and are generally employed by a particular type of person (the upper normie of some of the previous articles) to bolster a certain political viewpoint. The misconceptions about historical family structures though are more nebulous, and older; as we will see, having their origins in social theories developed as far back as the eighteenth century. They are also less tied to one side of the political spectrum. The left is disinclined to believe in any history that would cast the Western world as progressive compared to the non-Western one. And a certain segment of the right, in promoting things like tight extended families and teenage brides, seem to be envisaging some sort of generalised trad-life that owes more to premodern India than it does to the history of their own countries.

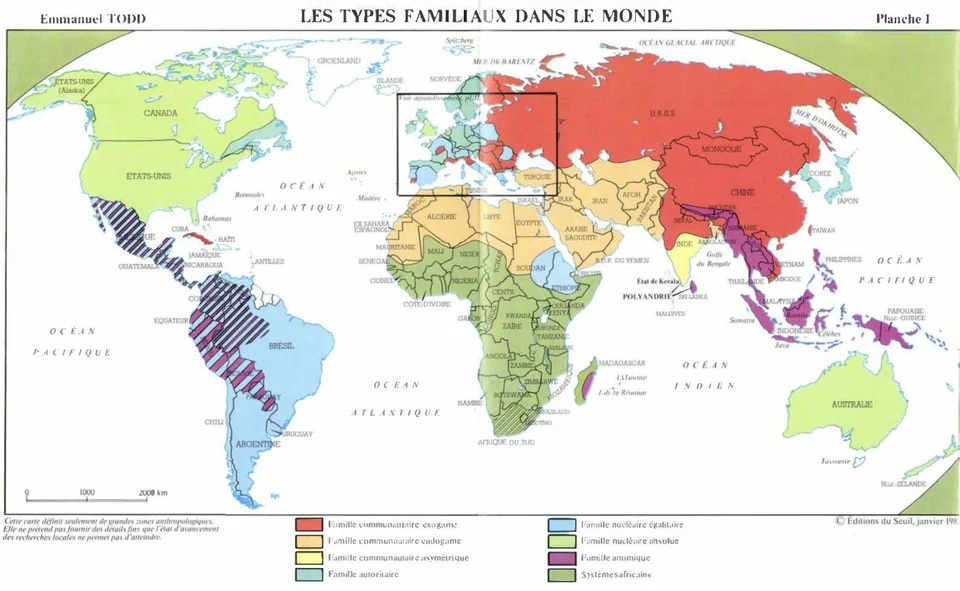

How much things really differed across the world historically

This is far too vast of a topic to comprehensively cover here, so below I’ll just describe the most relevant differences as I see them, looking mostly at Europe, India, China and the Muslim world, as these were the largest and most prominent civilisations. For deeper reading on these topics, see the works in the bibliography, particularly Emmanuel Todd’s The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems, Alan Macfarlane’s Marriage and Love in England: 1300 - 1840, and Joseph Henrich’s The WEIRDest People in the World. See also Alice Evans’s substack The Great Gender Divergence.

Age at marriage, cousin marriage, and extended versus nuclear families

In much of the world, girls were married in their early teens, and they would leave their own family to join their husband’s extended one, living together in one household (patrilocality). A well-known example of this is the traditional Indian joint family which was the dominant Indian family structure until the 1990s (Chadda and Deb 2013). Here, parents, their married sons, and the sons’ wives and children all lived in the same household, making up a collective economic unit1. Girls were married no later than puberty: the average female age at first marriage in India was thirteen in the early 20th century, with their husbands being in their late teens (Bhagat 2015). Once married, the girl would enter into a female household hierarchy with her mother-in-law at the top, then the wife of the eldest son, and then the wives of the younger sons. This system of very early marriage was made possible economically by the fact that there was no expectation that the teenage couple would establish their own household.

Marriages in India were, of course, arranged by the parents. In north India, a marriage partner had to be from the same caste but could not be from the same gotra (lineage), thus cousin marriage was proscribed. In South India however, both cousin marriage and uncle-niece marriage were preferred, and still were as of the 1990s, which saw rates of 47% in Tamil Nadu (Rao et al 2009).

Women in imperial China married later than in India: between sixteen and nineteen from the sixteenth century up until the 1960s. The average age for men was 21 from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries (Lee & Feng 1999: 65 - 72). As in India, the normative family structure was married sons living with their parents as a collective economic unit, with the household head holding absolute authority, (Lee & Feng 1999: 125), although in practice often only the eldest son remained. Marriages in China were also arranged, but as in north India, marriage within the same extended family was forbidden.

In the middle east, marriage was early and endogamous, preferentially between the children of brothers. Edward William Lane, a translator of The Thousand and One Nights who lived in Egypt in the 1820s, wrote that the usual age there for brides was between twelve and sixteen, and a few years older for men. Alexander Russel, who spent fourteen years in Aleppo in the mid 18th century, wrote in his The Natural History of Aleppo that the usual age of marriage for a girl was between fourteen and seventeen, but sometimes as early as twelve or thirteen.

Cousin marriage, specifically between the children of brothers, was preferred because the ties of brotherhood were more important than the marital bond. As Lane wrote:

“It is very common among the Arabs of Egypt and of other countries, but less so in Cairo than in other parts of Egypt, for a man to marry his first cousin. In this case, the husband and wife continue to call each other ‘cousin’ because the tie of blood is indissoluble; but that of matrimony very precarious”.

Similarly, in One Thousand and One Nights, you will repeatedly encounter this form of marriage held up as the respectable ideal (Todd 1985: 21). In the account of a merchant’s love for his wife it translates to “he loved her excessively, since she was the daughter of his paternal uncle”.

This ‘fathers brothers daughter’ (FBD) form of marriage, and the clan-based society that results, was characteristic of the Arab and Muslim worlds and remains so to this day. See Alice Evan’s Cousin Marriage and Islam for more on this2.

Europe, or at least western Europe, had a distinct marriage pattern, described most famously by the Hajnal line. One characteristic difference from elsewhere was that marriage took place later. For women in France between the 16th and 18th century it averaged between 21 and 27 (Bardet 2001), in southern Italy between the 16th and 18th century 22 ½, and in late 18th century Spain 23. In Britain it was even older, never younger than 24 for women from the 16th century onwards, except for in the baby boom years of the 1950s and 1960s. The earliest age I’ve found in Europe is from a study of Tuscany in the 15th century, which found that it averaged 19 for women, with a modal age of 16, and an average age of 28 for men (Herlihy and Klapisch-Zuber 1985: 205). The late marriage pattern is thus not universal across Europe, but it seems predominant, generally with the higher ages in the north west.

Cousin marriage was officially forbidden in Europe, a result of the long crusade by the church going back to the second half of the first millenium (see Henrich 2020). This was largely successful, although never completely: royals continued to practice it to cement family alliances, and protestantism relaxed the prohibitions.

Compared to today, families still held significant control over marriage partners, but this was counteracted by the relatively late ages at marriage and the fact that the church promoted marriage as a contract between the couple, not their families. The requirement for a mutual ‘I do’ in the marriage ceremony embodies this (Henrich 2020: 166). In northwest Europe in particular the consent of the couple was an essential element of marriage, and the marriage system was largely directed and managed by the young people themselves (Thornton 2005: 54). The idea of consent was not unique to Europe: Islamic jurisprudence also promoted the importance of mutual consent in the marriage ceremony, but this was counteracted by early age at marriage and the ‘father’s brother’s daughter’ cousin marriage norm.

Household structure in Europe mostly ranged from nuclear, as in England at least since the end of the high medieval period (see Macfarlane 1986), to the stem family, common in Germany, where the eldest son continues to live with his parents. In some parts of Europe, as in the Tuscan study I mentioned above, extended households defined by a patrilinear group were common, as in Asia, and the expectation was that married sons would continue to live under their father’s roof (Herlihy and Klapisch-Zuber 1985: 290). This communitarian family structure though seems to have been quite rare in Europe aside from in the east. See Todd’s The Explanation of Ideology for more on family structure in Europe and elsewhere.

Monogamy, polygamy, and patrilinear vs bilateral descent

Until European marriage norms started to spread around the world in the 20th century, polygyny of some kind was the most common type of marriage system. This either took the form of one man being permitted multiple wives, or of him being permitted one wife plus legally recognised concubines. Representative surveys of preindustrial human societies such as the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock 1967) have generally found that between 70% and 85% permitted polygyny. Naturally this does not mean that polygyny was practiced by a majority of the population across the world – the maths of the sex ratio doesn’t permit it. But the differences certainly affected elite practices.

Polygyny was accepted in Hinduism and practised by elite Hindus (and Sikhs). Hindu religious texts like the Manusmriti specify the allowed number of wives per caste and how co-wives should be treated. To take one, relatively recent example, Man Singh II (1912 - 1970), the Maharaja of the princely state of Jaipur until Indian independence in 1948, had three wives, while his predecessor had five and multiple concubines. In imperial China, multiple wives were not permitted but official concubines were (Lee & Feng 1999: 75 - 76). Concubines had a lower status than wives, but they were still officially recognised, and their children could be legitimate heirs.

In the Islamic world, men were permitted up to four wives, while concubinage with enslaved women was common among elites in all the major Muslim empires. Ottoman sultans frequently did not marry at all, and instead produced sons with a variety of concubines, often slaves imported from the Caucasus. Their sons would then fight it out to succeed him on his death. This system persisted right to the end: the last Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI (ruled 1918 - 1922), was the youngest of 42 siblings and half-siblings born to various concubines of his father. As Henrich goes into in more detail, the Ottoman system was thus an example of an exclusively patrilineal descent model, tracing descent only through the male line (Henrich 2020: 155).

Sub-Saharan Africa seems to have been the most extreme example of a polygynous society, one where a large percentage of women were polygamous wives. To a significant extent it still is, although this is declining: as of 1995, a ‘polygamy belt’ stretched from Senegal to Tanzania, in which it was common for a third of married women to be in polygamous unions. In Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Senegal, more than 60% of married women in 1970 were in polygamous unions, which had dropped to less than 40% in 2000 (Fenske 2015).

The particularly high rates in West Africa may be influenced by the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade which contributed to a sex imbalance by taking more men than women. However, rates in East Africa, from where more female slaves were taken, are still quite high. Some example numbers from survey data between 1990 and 2009 in Dalton and Leung 2014 are 33% of men in polygamous marriages in Senegal, 20% in Nigeria, 16% in Ghana, 16% in Uganda, 18% in Mozambique, and 9% in Kenya.

Christian Europe after about 1100 was the only major civilisation which did not permit polygyny or official concubinage. Unofficial concubinage was, of course, present, but a society’s ideals do have an effect even if not strictly followed, particularly on which heirs count as legitimate.

As Joseph Henrich describes in the ‘WEIRD families’ chapter of The WEIRDest People in the World, the church fought continually to impose the ideal of monogamy. In early Christian Germanic Europe, rulers often had many recognised concubines and fathered legitimate heirs with them, as you can see in the lives of the early Merovingian and Carolingian kings. For example Theuderic, son of founder of the Merovingians Clovis I, whose mother was likely a concubine, became a king after him just as did his sons by his recognised wife.

A last gasp of the old system can be seen in Robert of Normandy successfully naming William (the Bastard) his heir in the 11th century, despite him being his son by his mistress Herleva. Later on in Europe, the church fully imposed the monogamous ideal and something like this was no longer possible, as the struggles of Henry VIII to beget an heir indicate. Rulers, however, did often ‘acknowledge’ their illegitimate children by giving them titles and privileges (such as Charles II did with his various illegitimate children).

Unlike the Ottoman system, the European one was a bilateral descent model, where it mattered both who your father and your mother were for legitimacy. This, together with the requirement for monogamous marriage, and the development of primogeniture, are the reason why in Europe you occasionally got women inheriting the throne if a king had no legitimate sons, such as Isabella of Castille, Elizabeth I of England, or Maria Theresa of Austria3. It’s notable when looking at medieval and early modern history how much more common this was in Europe than Asia, where there were no established rules that permitted female succession. You occasionally got examples of where the rules were broken, generally by the mother or consort of an emperor, such as 7th-century Chinese empress Wu Zetian, but these were far rarer than in Europe.

Other differences: female seclusion, the treatment of widows, divorce, and female infanticide

All premodern societies, including Europe, practised seclusion of women from public life to some extent, especially elite women. But the extent of this seclusion differed quite radically. Bernard Lewis’s The Muslim Discovery of Europe contains various examples of the shock Muslims displayed at European women’s relative lack of seclusion. As one Syrian said of the Crusaders:

“The Franks have no trace of jealousy or feeling for the point of honor. One of them may be walking along with his wife, and he meets another man, and this man takes his wife aside and chats with her privately, while the husband stands apart for her to finish her conversation; and if she takes too long he leaves her alone with her companion and goes away.” (Lewis 2001: 286).

Similarly, India had the purdah system of female seclusion, while, as I’ll expand on later, something similar (terem) existed in Russia prior to Peter the Great’s reforms. China too secluded aristocratic women, with foot binding being a highly physical means of achieving this. Europe lacked this strict sex segregation; while the freedom of women was restricted, royal courts were mixed-sex environments.

Divorce was harder in Europe historically than in most of Asia. The Islamic world permitted divorce, as did imperial China. In these cases it was generally much easier for a man to divorce his wife than the other way around. In imperial China’s dishu system for example, permitted reasons for a man to divorce his wife included her indulging in excessive gossip, suffering from a severe illness, or being unable to bear a son. Today, access to divorce is generally seen as a feminist issue, but when you take into account the asymmetry that existed in premodern divorce practices, things get more complicated.

The treatment of widows differed significantly across the world. The Islamic world that offered them the most autonomy; widowed women re-marrying was an accepted practice. Catholic Europe discouraged it, but protestant Europe encouraged it; both Luther and Calvin supported it in their writing. China strongly discouraged it. India also strongly discouraged it for high-caste women, with the promotion of sati being the ultimate example of what esteemed conduct was for widows. In the Chinese and Indian case, the negativity around widow remarriage was linked to the extended family households: women were expected to stay and care for the dead husband’s parents.

Finally, female infanticide was the primary means of population control in late imperial China, with recorded rates for some years in certain populations reaching 40% of all female births. Male infanticide was practised too, but at lower rates (Lee & Feng 1999: 7). Female infanticide was also common in India, but forbidden in Christian Europe and the Islamic world.

The intellectual history of the misconceptions

Considering all these historical differences, where did the misconception of an undifferentiated ‘traditional past’ come from? Arland Thornton’s 2005 book Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life provides a good explanation. For Thornton, ‘reading history sideways’ (see here for a summary) is the tendency to assume that historical processes are universal and linear and that societies move along them from less to more developed.

Thornton identified the origin of these ideas in the first European writers to write cross-cultural comparisons of world civilisations, starting in the 18th century. They observed that family structure in places like India or China was very different from what they were familiar with, and therefore assumed that their own countries had been like this in the past. This misconception was strengthened once non-European countries started to modernise, as they increasingly adopted European family structures (initially as state policy, and later organically). This made it seem like the adoption of these family structures was simply part of economic modernisation.

These ideas were formalised in the modernisation theory of the 1950s and 1960s, which developed broad models of the demographic transition that accompanied modernisation, which were assumed to apply everywhere. Talcott Parsons, who was highly influential on modernisation theory, saw small nuclear families as the quintessential modern form of an individualist, liberal, democratic, and economically dynamic society.

As a result of all this, the idea that the West had relatively recently gone through the same transformation that the developing world was going through at that time became widespread. Thornton notes that he found it difficult to disabuse his students of the idea of ‘the great family transition’, writing that “this notion is so strongly embedded in American culture” (Thornton 2005: 108).

The first real challenge to the ‘developmental paradigm’ started in the 1960s from scholars associated with the Cambridge Group for the History of Population & Social Structure (Campop), founded in 1964. As this post describes more fully, Peter Laslett, a cofounder of the group, discovered in the 1960s that, contrary to the large patriarchal families he had expected to find in the parish records of 17th century England, families had actually been predominantly small and nuclear. He and others in the group developed these ideas in works such as Household and Family in Past Times (1972). Other authors I’ve drawn upon in this article were also associated with Campop, such as Alan Macfarlane and Emmanuel Todd.

These scholars were conscious at the time that they were correcting widespread misconceptions. Peter Laslett wrote an article in the London Review of Books in 1980 about some of them, in particular, the one that the nuclear family was a modern invention. However, despite all this work, now dating back sixty years, disproving the old developmental paradigm of family structure, my experience is that popular opinion on this subject is still heavily influenced by it, and that people continue to read history sideways.

Becoming modern was becoming Western

Something that I think is also underappreciated is the extent to which countries wishing to modernise deliberately adopted European marriage and family norms. Generally this happened at a top-down, state driven level prior to any significant organic development.

The first state to attempt this was Russia. Peter the Great’s reforms from the end of the 17th century aimed to produce a modern, European style state with a ‘service nobility’ that was dependent on it. His reforms were widely targeted: well-known ones include restructuring the military, taxing beards, and forcing men to replace their robes with trousers, but he also attempted to transform marriage and family life for the elite.

A decree of 1702 mandated the free consent of the bride and groom in marriage, and the minimum age was raised to 17 for women and 20 for men4. Traditionally, a more Asian system of early and arranged marriages had been the norm – foreign visitors to Muscovy in the 16th century noted that girls were married at twelve or thirteen, and boys at fifteen or eighteen (Levin 1989: 95-96)5. Prior to Peter’s reforms, aristocratic women had lived lives of seclusion (referred to by historians as terem), similar to the system of purdah as experienced by women in India. In 1718, because he wanted a European-style court, Peter started to promote mixed-sex assemblies with socialising and dancing, ending the terem system. The impact of these reforms was limited to the aristocracy, but they did substantially succeed in shifting social life in this class from an Asian to a European model.

Other modernising countries followed from the 19th century. Japan ended legal recognition of concubinage between the late 19th and early 20th century (although the end of arranged marriage did not come until the postwar era). The Republic of Turkey’s reforming, Swiss-influenced civil code of 1926 abolished polygamy, and in one of its subsequent revisions it started requiring the explicit consent of both parties to marriage. In China, official concubinage was criminalised in various laws from the 1930s to the 1950s, while the New Marriage Law of 1950 required consent of both parties and allowed officials to reject marriages they deemed to have been forced. In India, polygamy for Hindus was formally abolished with the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, which also required the free consent of both parties.

What you see in these examples is that the adoption of Western marriage and family norms was initially a top-down state driven modernisation effort. Part of this may have been a recognition that large, patriarchal extended families or clans were antithetical to the strong, modern state and dynamic industrial economy that these countries saw in the West and wanted to emulate. But my guess is that to a large extent the modernisers in these countries imported aspects of Western culture simply because they observed that ‘this is what it is to be modern’.

In all cases it took time for the real societies in question to reflect these new norms, but eventually, the experience of modernisation led to their advance in a more organic way, as the increasing power of central states and industrialisation dissolved the context in which patriarchal clans function. Even in a country like Qatar, for example, which never went through the same state enforced Westernisation of marriage norms as other countries did, rates of polygamy are falling.

However, significant differences remain. Cousin marriage remains common in the Muslim world, while polygamy remains widespread in sub-Saharan Africa. It’s telling that unlike in Asia, African countries were less likely to criminalise polygamy as they started to develop, and indeed, Kenya formally legalised polygamy in 2014 – previously it had been illegal under the British-inspired civil code, though permitted in practice. These places are among the least developed in the world, so perhaps the modernisation theorists were right, and the Western family system fits best with a modern economy and society.

However, looking back at the history, the prestige of the West, driven by its power and wealth, clearly played a vital role in the spread of its marriage and family system. As Arland Thornton put it, “Western family ways are not inherently appealing to all, but have their attraction primarily through their connection with health, wealth, power, and progress” (Thornton 2005: 159).

The future of the Western marriage and family system

As the relative prestige of the West falls, and it becomes just one example of a wealthy, modern parts of the world (and in many ways, a poorly run example), will this mean an end to the dominance of the Western marriage and family model? Absent state collapse, I don’t foresee a return to extended family clans, and it’s hard to see any of the old models making a comeback (although Steve Sailer has theory that an alliance of rationalist polyamorous tech workers and immigrant African polygamists could push to legalise polygamous marriage under a banner of anti-racism and ‘love is love’). On the whole, the world is still moving more towards the Western model than away from it.

However, the model has been breaking down for some time within the West itself. Late marriage has increasingly become never-marriage, and nuclear families have, for the bottom part of society, been replaced with a more chaotic system of single mothers often supported substantially by the state. Even the neolocal nuclear household is under threat, as young people struggle to afford properties they could raise a family in. Meanwhile, mass, unselective immigration policies have reintroduced clannish family systems into Western countries for the first time in centuries, exploiting Western societies in appalling ways, such as with the Pakistani grooming gangs in Britain. More recently, the emerging aesthetics of the modern manosphere are that of a post-white Western world, where figures like Andrew Tate promote a distinctly Middle Eastern morality, emphasising male brotherhood and solidarity above all, with women relegated to a neo-harem.

Even more fundamentally, birthrates are now cratering worldwide. While there’s nothing inherently fertility-retarding about the Western family system, clearly there is something about modern society in general that is. The floor is open for a different system that can reproduce itself, as long as it can do this faster than it loses its children to the mainstream. See Eric Kaufmann’s book Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? for more on this.

The dangers of not appreciating the deep history of the differences in marriage and family structure

In addition to being factually wrong, I think the failure to appreciate differences in marriage and family structure over history has a malign effect on Western societies. A failure to appreciate the differences in history also tends to mean a failure to appreciate the differences today. Sometimes the whole subject is ignored, while sometimes it’s assumed that a modern environment will quickly and inevitably produce modern structures. There is a widespread lack of appreciation of what cultural differences really mean, not surface level things like food or music, but the structure of social and family life itself. These failures of imagination have contributed to various disasters. They range from the failure of nation-building in post-Taliban Afghanistan, to failing to control chain migration from extended family societies6, to allowing grooming gangs to run unchecked in English towns. I hope that this article goes some way to correcting them.

Bibliography

Bardet, J. P. (2001). Early marriage in pre-modern France. The History of the Family, 6(3), 345-363.

Bhagat, R. B. (2015). Do Early Marriages Persist in India?. Paper presented at the National Seminar on the Marriage and Divorce in a Globalised Era: Shifting Concepts and Changing Practices in India, organised by Centre for Culture and Development held on 10-11th April, 2015, Vadodara.

Chadda, R. K., & Deb, K. S. (2013). Indian family systems, collectivistic society and psychotherapy. Indian journal of psychiatry, 55(Suppl 2), S299-S309.

Dalton, J. T., & Leung, T. C. (2014). Why is Polygyny More Prevalent in Western Africa? An African Slave Trade Perspective. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 62(4), 599-632.

Darwin, G. H. (1875). Marriages between first cousins in England and their effects. Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 38(2), 153-184.

Evans, A. (2023, 1st October). Cousin Marriage and Islam. The Great Gender Divergence.

Fenske, J. (9th Nov 2013). African polygamy: Past and present. Vox EU / Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Fenske, James. (2015) African Polygamy: Past and Present. Journal of Development Economics, 117 . pp. 58-73.

Goody, J. (1996a). Comparing Family Systems in Europe and Asia: Are there Different Sets of Rules?. Population and Development Review, 1-20.

Goody, J. (1996b). The East in the West. Cambridge University Press.

Hajnal, J. (1982). Two Kinds of Preindustrial Household Formation System. Population and Development Review, 449-494.

Henrich, J. (2020). The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. Penguin Books.

Herlihy, D., Klapisch-Zuber, C. (1985). Tuscans and their Families: a Study of the Florentine Catasto of 1427. Yale University Press.

Lane, E. (1842). The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians.

Laslett, P. (1980). Characteristics of the Western European Family. London Review of Books, Vol. 2 No. 20 · 16 October 1980.

Levin, E. (1989). Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs, 900-1700. Cornell University Press.

Lewis, B. (2001). The Muslim Discovery of Europe. W. W. Norton & Company.

Lee, J. Z., & Feng, W. (1999). One Quarter of Humanity: Malthusian Mythology and Chinese Realities, 1700–2000. Harvard University Press.

Macfarlane, A. (1986). Marriage and Love in England: 1300 - 1840. Basil Blackwell.

Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic atlas: a summary. Ethnology, 6(2), 109-236.

Rao T. S., Prabhakar A. K., Jagannatha Rao K. S., Sambamurthy K., Asha M. R., Ram D., Nanda A. Relationship between consanguinity and depression in a south Indian population. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;51(1):50-2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44906. PMID: 19742204; PMCID: PMC2738415.

Reid, A. (2024, 11th July). What age did people marry in the British past?. The Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure blog.

Russel, A. (1794). The natural history of Aleppo.

Scheidel, W. (2009). A peculiar institution? Greco–Roman monogamy in global context. The History of the Family, 14(3), 280-291.

Schürer, K., Szreter, S. (2024, 11th July). How modern is the modern family?. The Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure blog.

Todd, E. (1985). The Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems. Basil Blackwell.

The Thousand and One Nights. Translated by Edward William Lane, 1912.

‘The voyage wherein Osepp Napea, the Moscouite Ambassadour returned home into his Countrey’. In Early Voyages and Travels to Russia and Persia. Hakluyt Society, 1886.

Thornton, A. (2005). Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. The University of Chicago Press.

Wetherall, W. (17th February 2025). Social status laws in Japan, Caste, class, and titles of nobility since 1868.

Related articles:

The joint family was the ideal, though note that in reality family sizes in India were often smaller. See Hajnal (1982) and Goody (1996a).

As an aside, there’s a somewhat counterintuitive argument, also relevant in the south Indian case, that in an arranged marriage system, cousin marriage is actually better for women, as on her marriage, she will not be an outsider entering another family’s home at the bottom of the hierarchy, but family.

This only happened in countries that did not practice Salic law, as France for example did.

This was much higher than in, say, England in the same period (12 for girls and 14 for boys), but as we have seen, the actual ages people tended to marry was much higher in England than Russia.

The account Levin draws on is from the 16th century account ‘The voyage wherein Osepp Napea, the Moscouite Ambassadour returned home into his Countrey’, p. 375).

While also making life unnecessarily difficult for people from nuclear family societies who want to marry a foreigner

You see how and why Asian feminists view the specter of legalized polygamy in the west as a REAL threat? The entire poly pedo complex collapsed under communist enforcement which is why so many Chinese women are staunchly Communist.