Folk Beliefs of the Upper Normie III: “Europe was a Backwater Before Colonialism”

How a mistaken argument from the California School in the 'great divergence' debate became conventional wisdom

This article is the third in a series on modern folk beliefs. In the series so far:

“Europe was a Backwater Before Colonialism”

See the introduction to the first article for the full idea of the upper normie and their folk beliefs: below is an abridged version.

I have always liked the concept of the upper normie. An upper normie is someone who holds conventional mainstream opinions but is a bit more intelligent than the average and thus considers themselves to be more sophisticated than the normal normies. Common examples of the upper-normie worldview in Britain are the #FBPE movement, James O’Brien fans and The Rest Is Politics listeners.

Every society has its folk beliefs: sayings and stories about the world that are widely held yet not grounded in fact, and I have come to think of much of the upper-normie worldview as a collection of these folk beliefs. These are not the old sayings about health and wealth that might be passed down via your grandmother, but somewhat muddled and simplistic ideas about history, nationhood, economics, colonialism, race etc. that originated from academia, the media, the cultural industries, governments and NGOs.

“Europe was a backwater before colonialism”

This folk belief holds that before the colonial era (i.e. around 1500) Europe was a poor and primitive backwater compared to the civilisations of Asia, particularly those of China, India, and the Middle East. The belief has a counterpart in a related one, which I may deal with in a future article, that Europe’s subsequent wealth can only therefore have been acquired via slavery and colonialism.

This ‘Europe as backwater’ belief can be found in the pages of The Guardian (“In the 15th century, China was the most advanced civilisation in the world, while Europe was a backwater”) and the Financial Times (“how did Europe, a backward continent with miserable weather and dirty little cities, for a time grow faster than the rest of the world?”). It’s found in some of the bestselling popular history books of the past few decades. Niall Ferguson, one of the most prominent popular historians of the 2000s and 2010s, wrote in the introduction to his 2011 book Civilization: The West and the Rest (reviewed in The Guardian article cited above) that “Western Europe in 1411 would have struck you as a miserable backwater” (Ferguson 2012: 4). Peter Frankopan, in his 2015 international bestseller The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, writes that as a result of the European discovery of sea routes to America and Asia, “suddenly, western Europe was transformed from its position as a regional backwater into the fulcrum of a sprawling communication, transportation and trading system” (Frankopan 2017: xviii).

In my previous article in this series I described how the modernist approach to the study of nationalism has provided the intellectual basis for the widespread belief that nations are modern creations. While the historical debate on the question of the ‘Great Divergence’ (when and why Europe began to technologically and economically outstrip the rest of the world) has more intellectual diversity than that about nationalism, it is a similar story here. Various authors, in an attempt to counter the eurocentrism they perceived in the discourse, have done all they can to try and prove Europe’s backwardness in the centuries before European dominance became indisputable in the 18th or 19th centuries. 1500 is often chosen as the example year representing the beginning of the colonial era, so I will use that year here too.

For a few different reasons, including the rise of China from the late 90s, and the trend towards self-abasement in the broader culture, this ‘backwater’ rhetoric found a ready audience and became a new conventional wisdom. However, as we will see, this new conventional wisdom is completely wrong. Below I’ll provide a history of the debate, then a description of the actual technological and economic situation in Europe compared to Asia in 1500 and in the years afterwards (I’m focusing on Western Europe but will use ‘Europe’ for convenience). Finally I’ll describe why I think this belief has become so widespread.

The history of the ‘Great Divergence’ debate

The original approaches to the question of the great divergence tended to look at broad social structures rather than the specifics of technology (which the authors would not have had access to). They contrasted dynamic Western capitalism with stagnant oriental societies, as in Marx’s idea of an ‘Asiatic mode of production’ of self-sufficient, communal villages, or in Weber’s books contrasting capitalist Protestant Europe with China and India. The 1980s and 1990s saw works that took a more detailed look in this same vein, such as Eric L. Jones’s The European Miracle, published in 1981, and David Landes’s The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, published in 1998. These located the roots of European exceptionalism, and thus of the great divergence itself, as going back to the 15th century and beyond.

The California School and countering eurocentrism

The loose grouping of scholars termed the California School was a reaction to what they saw as a dominant and eurocentric narrative. They aimed to show that there was nothing exceptional about Europe in technology, science, living standards or social organisation compared to Asia until the 18th or 19th centuries, and for some of them, that Asia had the better claim to be more advanced during this period (Vries 2010, Goldstone 2009). They also often explicitly stated that their intentions in writing were to combat eurocentrism.

There are two types of California School work – the first type emphasises the fundamental similarities of pre industrial revolution societies, by showing that anything especially advanced or dynamic that existed in Europe also existed in the advanced civilisations of Asia. The second type goes further and tries to show that Europe was backward (and indeed a ‘backwater’) compared to these Asian civilisations.

Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence (first published in 2000) is the best-known example of the first category. Pomeranz identifies the consensus at the time he was writing as being that of Eric Jones’s aforementioned The European Miracle, in which Europeans were uniquely wealthy in human and physical capital long before industrialisation (Pomeranz 2021: 10, 31). Pomeranz’s intention was to show that the pre industrial revolution world was in reality one of ‘surprising resemblances’, where any technological or institutional advances Europe possessed were also found elsewhere (Pomeranz focuses on China, particularly the advanced Yangtze delta region).

For Pomeranz, the divergence did not come until the 19th century, and was not based on any special characteristics of European civilisation, but was due to contingent factors like the ‘ghost acres’ provided by the colonisation of the Americas, and the easily accessible coal in Britain. Pomeranz has since revised his view of divergence to the mid 18th century (see his articles of 2011 and 2017), but his main argument of a ‘late divergence’ remains.

Then there is the second category, those who make the ‘Europe as backwater’ argument. Andre Gunder Frank in his ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age (1998) aimed to show that before 1800 there was a sinocentric world economy in which a less productive, less advanced Europe had only a marginal position. His argument focuses mostly on Europe’s negative balance of trade with Asia; how Europe had to use American silver to pay for Asian goods as there was little demand there for its own. As I will go into in more detail later, this is a broadly accurate description of trade relations at the time. However the problem for the argument is that you cannot use a small amount of intercontinental trade in mostly non-competing goods (i.e. goods that could not be produced in Europe for climatic reasons) to prove a ‘Europe as backwater’ thesis.

An extreme example of the second category is John Hobson, who, in his The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (2004), is explicit that countering eurocentrism is his primary goal in writing the book. He tries to prove that the credit for every single European invention or achievement should in reality go to Asia, for example that the ultimate origin of the steam engine is Chinese because they invented gunpowder and understood atmospheric pressure (Hobson 2004: 210). Hobson makes a few reasonable points about the historical balance of trade and about advanced Asian technology such as in Chinese iron production, but he is so keen to prove his point about Europe’s backwardness that he often strays into ludicrousness. He claims among other things that Arab sailor Ahmad ibn-Mājid sailed around Africa before Europeans did1, and that St Augustine was black (he was really of Berber origin). Most incredibly, he appears to think that most of the earth’s landmass is in the southern hemisphere but that the eurocentric Mercator projection erroneously shows the opposite (Hobson 2004: 5-6).

Overall, some of what the California school argued was reasonable (e.g. Pomeranz’s points about the advanced civilisation of China), while other arguments (Europe as a backwater in 1500) were less so. But it is these latter arguments which have been especially influential and have formed the basis for a widespread false belief.

Attempts to quantify the great divergence

Concurrently with the works of the California school, various scholars attempted to come at the question by quantifying historical levels of development for different parts of the world. I share the skepticism of those like Gregory Clark or Patrick O’Brien who think that the paucity of data means it is impossible to provide meaningful measures of fundamentally modern concepts like a country’s GDP per capita for the pre-modern world. There is a risk that putting numbers on things makes them seem more certain than they really are. However, the estimates are worth describing, and I think they are at least directionally correct.

The work of Angus Maddison is the best known example of this approach. He claimed that while China was the world’s leading economy in terms of per capita income in 1300, outperforming Europe in levels of technology, by 1500 Western Europe had overtaken it on both counts (Maddison 2003: 157). The GDP per capita numbers (in 1990 international dollars) he estimated for 1500 are $771 for Western Europe, $600 for China, Korea, Iran and Turkey, $550 for India and $500 for Japan (Maddison 2003: 117). Since his death the Maddison Project has continued his work – the numbers have changed in their latest (2023) estimates of GDP per capita, but the broad pattern is the same.

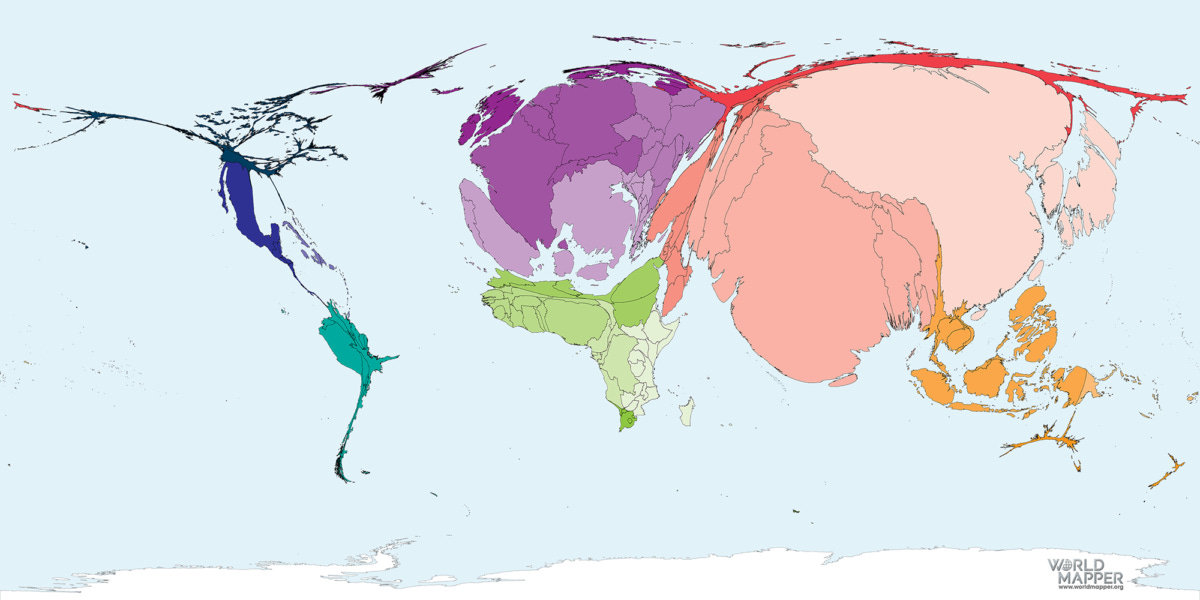

The map below is based on Maddison’s original 2003 numbers for GDP per capita in 1500. As mentioned these numbers are estimates based on fragmentary sources, but I think that the map does at least correctly give a sense that Europe was, together with the regions centred on China and India, one of the three core economic centres in 1500 (as it was of population, which in a pre-industrial world, was a highly correlated metric).

A more recent example from 2017 (on which some of the most recent Maddison Project estimates are based) is Stephen Broadberry who finds that the most advanced areas of Western Europe pulled ahead of China (as a whole) in GDP per capita by the 1400s at the latest (and were far ahead of India and Japan). The figures he gives for 1500 (in 1990 international dollars) are $1114 for England, $1483 for the Netherlands, $1483 for Italy, and $858 for China (he gives figures for Japan and India from 1600 only, at $605 and $682 respectively).

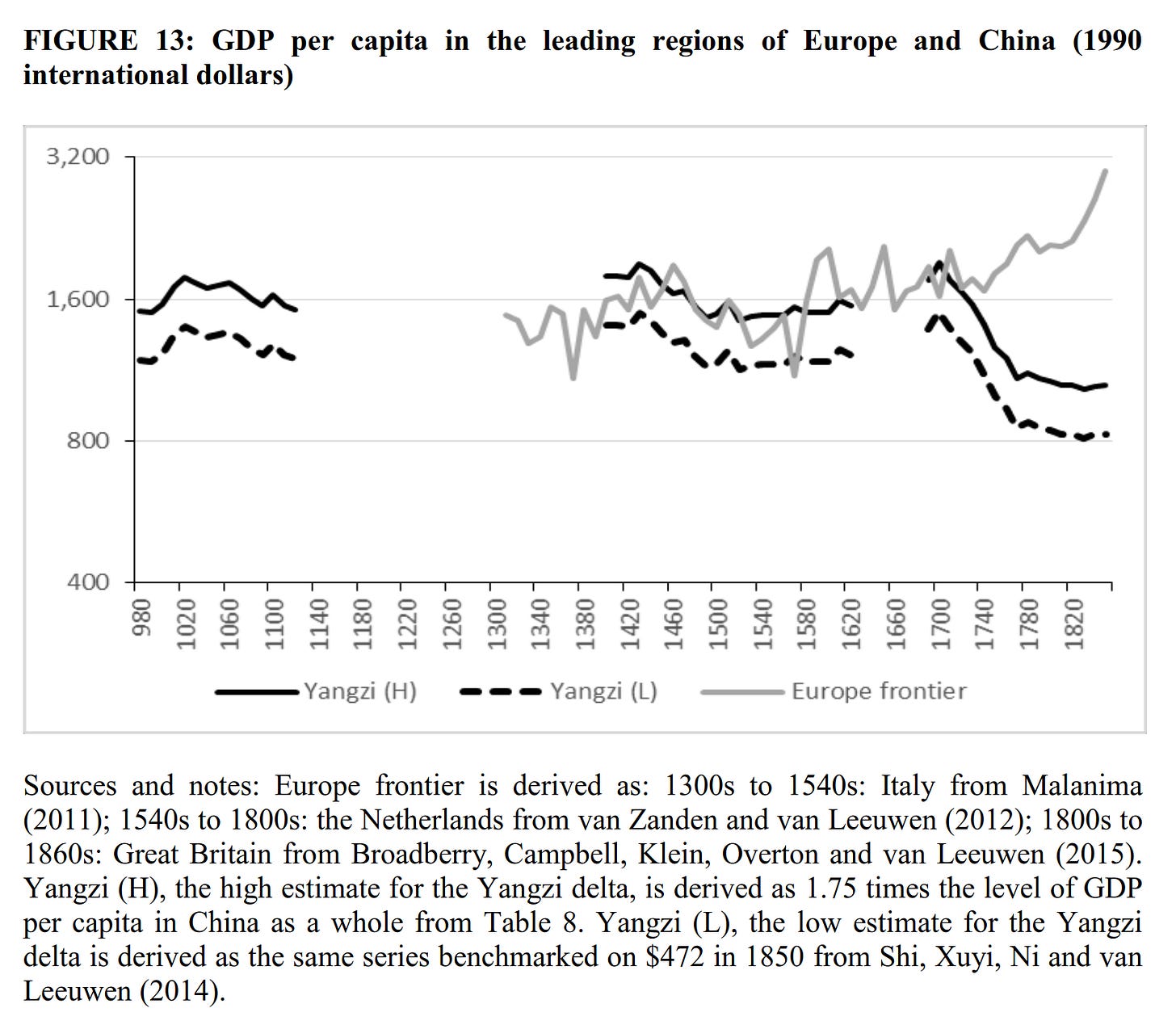

As many including Pomeranz have noted, comparing particularly wealthy Western European countries with the whole of China is not a fair comparison. The most advanced area of China – the Yangtze delta – Broadberry finds to have been on a par with or slightly below the most advanced areas of Europe from the 15th to the early 18th century, as in this table from the paper. (Note that the Chinese decline in per capita GDP after 1700 is due to a population boom in the absence of significant productivity increases, rather than an absolute GDP decline).

On the related question of technology, a paper from 2021: Comin, Easterly and Gong’s Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 BC? assembled indices of technology adoption (from 0 to 1) for different parts of the world at different points in history. It tells a similar story to the GDP per capita figures, with the figures for 1500 being Europe as a whole 0.86, Western Europe 0.94, China 0.88, India 0.7 and the Arab world 0.7.

Overall then, the most recent attempts at quantification of the great divergence question find that the advanced parts of Europe were equally or more advanced than similar areas in China around 1500, both of which were more advanced than regions elsewhere.

The current state of the debate

The academic consensus now seems to be that it was in the early 18th century that advanced regions of Europe pulled decisively ahead of the advanced ones of Asia (Pomeranz 2017, Bisin & Federico 2021: 760-768). However, a great divergence in the 18th century does not mean that Europe was a backwater in the centuries prior to this, and it’s only the most tendentious elements of the California school who make the case that it was. As we will see from a historical survey of the technology of the period, this rhetoric cannot be supported.

Technology in Europe and Asia in 1500

If we were to go back further to the year 1000 AD, and conceive of Europe as Latin Christendom (i.e. excluding the Byzantines) then there would be some truth to the backwater idea, at least compared to the most advanced areas of Asia. But the period to 1500 saw Latin Christendom come to fruition as a new civilisation, one which in many ways was on humanity’s technological frontier. Carlo Cipolla’s Before the Industrial Revolution (1993) provides a good overview of the changes over this period, below is a partial summary drawing on this and other sources.

Initially little of this transformation involved innovations that were not found elsewhere. Some, like gunpowder, paper or the compass, originated in China and were then transmitted to Europe via the silk road or middle east. Others involved the further development of longstanding technologies, like the spread of the water mill into new industries. Others may have been independently developed, like the blast furnace or movable type, but had also previously been invented in China. Towards the end of the period though Europe began to produce innovations of its own.

There had already been an increase in the use of water mills for several centuries; the Domesday book in 1086 recorded 6,082 of them in England (Holt 1988: 8). In the high middle ages they began to be used for other purposes, not just for milling grain as had been the case before, but also for brewing, fulling cloth, sawing logs, turning lathes, and in iron and paper production (Cipolla 1993: 140 - 141). Additionally the vertical windmill – which turned its blades on a horizontal axis (i.e. in the classic Dutch style) – was developed in north west Europe in the 12th century. This type was not found elsewhere in the world where they continued to use the less efficient vertical axis (panemone) windmill. The blast furnace, in which iron ore is completely melted into liquid iron, had long been used in China, but the rest of Eurasia, including Europe, used the bloomery, in which iron ore could only be heated until it was malleable but not liquid. From the 13th century though, the blast furnace began to replace the bloomery in Europe, increasing the availability of iron tools.

In construction, there was the development of more advanced architectural techniques used in gothic cathedral building from the 12th century (the spire of Lincoln cathedral, to give one example, made it the tallest building in the world from its construction in the early 14th century until its collapse in 1548). Canal locks in the modern sense with double gates (‘pound locks’) appeared in Europe in the 14th century; they only otherwise existed in China.

The most advanced part of Europe in this period remained northern Italy. City states like Venice and Genoa had grown their initial wealth as conduits to Asia, but their own industries had begun to become more impressive in this period. Silk first became known to Europeans via the Arab world, who had ultimately acquired it from China, and the European silk industry first developed here from the 11th century. Glassmaking was notably advanced: Venetian glass from the island of Murano became the industry leader, displacing Syrian glass (Findlay & O'Rourke 2007: 129). Vision-correcting glass spectacles were first invented in northern Italy at some point in the late 14th century, and were not known elsewhere in the world.

Europe’s population expanded greatly over this period, more than doubling from around 32 to 71 million and growing faster than any other area of the world according to Maddison’s estimates (Maddison 2003: 376). The growth was particularly strong in northern Europe, the population of which roughly trebled between 1000 AD and the black death in 1348. Broadberry et al. (2011, Table 6) estimate that England’s population grew from around 1.7 million in 1086 to 4.8 million in this period. This increase was enabled in large part by the adoption of new agricultural technologies. The timelines of exactly when these became widespread are disputed (see Roland 2003), but two examples are the heavy mouldboard plough which brought new land into cultivation, particularly in the heavy soils of northern Europe, and three-field crop rotation, which increased agricultural productivity. Agriculture in large parts of south and east Asia remained more productive, though aside from in China (for example with their ploughs and seed drills), there’s not much evidence that this was due to more advanced technology rather than a more favourable climate.

The black death in the mid 14th century killed huge percentages of the population (nearly half in England according to Broadberry’s estimates), but in some ways this accelerated Europe’s transformation. One effect was hastening the replacement of feudalism with a market economy in Western (but not Eastern) Europe, due to the increased bargaining power of labourers (Jedwab et al. 2022). This was also the period that saw the beginning of the rise of North West Europe over the Mediterranean. Unlike most of Europe for example, Britain in particular did not see a decline in per-capita incomes after the initial boost caused by the black death (Bisin & Federico 2021: 766).

The development of the printing press using movable type saw the spread of a print culture with no parallel outside east Asia (where a well developed woodblock printing industry existed in China, and also to an extent in Korea and Japan). Movable type (but not the printing press) had also been invented in China and Korea earlier than in Europe, but had not become widespread, likely due to the large number of characters in East Asian scripts. Outside of East Asia and Europe, there was little printing at all.

An area that was genuinely pioneering was clockmaking. China and the Muslim world had sophisticated water clocks (Su Song’s 11th-century water-powered astronomical clock in Kaifeng and the Jayrun Water Clock in 12th-century Damascus are some well-known examples), as did Europe. But the mechanical clock powered by weights and with a verge escapement that converted the continuous force of the weights into the regular ‘tick’ was a European innovation developed around the late 13th century. These clocks soon became common in public places such as cathedrals and town squares. Later on, in the 15th century, spring-driven clocks appeared, which allowed them to be made smaller and thus more widespread.

These developments in clockmaking had no parallel elsewhere in the world, and as we will come to later, clocks were one of the innovations that most impressed the Chinese once Europe made direct contact in the 16th century. European advances in clockmaking also later became crucial to the industrial revolution (Allen 2009, ch. 8 – Cotton). For more on the development of clockmaking in Europe during this period, see Cipolla’s Clocks and Culture 1300 - 1700 or Landes’s Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World.

The result of all this was that by 1500 Europe’s relative backwardness compared to the other advanced civilisations of Eurasia had largely been eliminated. The Islamic world and India remained sophisticated civilisations, but by this point they did not seem to possess any particular advantages over Europe, except for in things that could not be produced in Europe for climatic reasons like cotton textiles. The only possible exceptions I am aware of are in some aspects of metallurgy, e.g. the production of wootz/Damascus steel using a crucible process originating in India, which was admired by Europeans long after 1500. Meanwhile Europe saw innovations that were not found in India or the Islamic world – in mechanical clocks, printing, glass manufacture, and naval firearms. As we will see later, international trade balances are not a sufficient measure of civilisational advancement in this period, but it is noteworthy that in areas such as the manufacture of glass and some textiles, the historic relationship of Europe as importer of manufactured goods from the Arab world had reversed by 1500 (Findlay & O'Rourke 2007: 127-129).

China though still remained exceptional in various ways. Chinese agriculture had long used ploughs with curved iron moldboards, which were more efficient than European ones. This type of plough was only developed in Europe (in the Netherlands and Britain) in the 17th and 18th centuries, and may have been influenced by Chinese examples. Chinese agriculture also used the seed drill, while evidence of a seed drill in Europe does not exist before the mid 16th century (a patent in the Venetian senate) and it did not become widespread until much later. Chinese iron production was also advanced, using coke driven blast furnaces from the 11th century (for comparison, Abraham Darby I’s novel-for-Europe coke driven blast furnace of the early 18th century was a key technology in the British industrial revolution). And as we will come to shortly, China manufactured porcelain more advanced than European earthenware. However as I will describe in the next section, Europe did possess several technological and scientific advantages over China by 1500.

Overall, technological differences between the advanced civilisations of Eurasia were relatively minor at this point compared to what came later, though Europe and China seem to have been somewhat more sophisticated than the others. In particular, Europe’s edge in mechanical objects, optics, and some aspects of (particularly naval) firearms would prove crucial in later centuries and ultimately to the industrial revolution.

Europe’s early encounters with Asian civilisations after 1500

One of the leading arguments of the ‘anti-Eurocentrists’ is that once Europeans did succeed in sailing around Africa and encountered Asian societies, they found themselves in the position of powerless and backward barbarians who had nothing to trade. This is a core argument of the works of Frank and Hobson that I mentioned earlier.

It’s true that Europeans were generally not able to exert military power on land over Asian societies in the 16th and 17th centuries (the Spanish conquest of the Philippines being an exception), though this is hardly surprising given the vast distances involved and relatively small differences in levels of technology. It is also true that there was much more demand in Europe for products from Asia than vice versa, and that Europeans paid for Asian products predominantly with (American) silver rather than with European goods, for which there was little demand. But using this idea of a balance of trade as a measure of civilisational advance or backwardness is misleading.

As Kees Terlouw points out in his review of Frank’s ReORIENT, international trade was, given high transport costs, such a tiny percentage of output anywhere that it cannot tell us all that much about economies at the time. International trade in 1500 is estimated at a maximum of 2.5% of world GDP in 1500, growing only to a maximum of 5.5% in 1600 and 1700, and 8% in 1800, compared to 50-60% today.

More importantly, the vast majority of these internationally traded goods were ‘non-competing’ goods. Things such as spices and tea could not be grown in Europe, and nor could the cotton that was the input to India’s textile export industries. Spices, for example, made up nearly all of Portuguese imports from Asia in 1518, and these ‘non-competing’ goods, deriving from natural sources that only occurred in Asia, always made up a majority of European imports from Asia into the 17th and 18th centuries (O’Rourke & Williamson 2002: 6). The European climate meanwhile did not produce similarly attractive non-competing goods for Asian markets. Wool, for example, is not as useful a raw material for making most fabrics as cotton is, especially for Asian climates.

The only real manufactured ‘competing goods’ that were imported from Asia to Europe were Chinese porcelain and Chinese silk. European pottery producers could make earthenware and stoneware, often in imitation of Chinese styles (e.g. Delftware), but could not produce porcelain itself until the 18th century (first made in Meissen, near Dresden, in 1710). Europe also still imported Chinese silk despite having a domestic silk industry (centred in Italy and France).

Again we can see the difference between China and the other civilisations of Asia. China, on which the most convincing works of the California School focus, is the only place where there are grounds for claiming that it was more advanced than Europe around 1500. Early European travellers of the 16th century certainly considered China to be more advanced than the other societies they were coming into contact with in the Indian Ocean. See the Technology - Perceptions of Backwardness: Qualified Praise section in part 1 of Michael Adas’s Machines as the Measure of Man.

However, China was not more advanced in all areas. A Chinese fleet defeated a Portuguese one at the battle of Sincouwaan in 1522 but China subsequently adopted the Portuguese breech-loading cannons, which were later used on the northern frontier. Europeans, together with the Ottomans, generally played the role of diffusing the most advanced firearms technology to the rest of the world in this period (Di Cosmo 2001).

Once the Jesuits led by Matteo Ricci entered the Chinese imperial court in the late 16th century, they found that European astronomical knowledge was more advanced than that of China. For example the Jesuits could predict solar eclipses better than the Chinese, and they found that Chinese cartographers still conceived of the world as flat. They also found that European clocks were more advanced than the water clocks in China, and that they made impressive gifts for officials and to the imperial court. European clocks began to be exported to China, marking an exception to the general rule of Europe importing Chinese goods (Cipolla 1977: 80 - 90, Bevan 2017).

There is a famous line from the letter sent from the Qing dynasty’s Qianlong emperor in response to the British 1793 Macartney Embassy’s request for trade liberalisation: “our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no product within its own borders.” But China had been importing European clocks for centuries, and the Qianlong emperor himself (an early exponent, at least officially, of the ‘Europe as backwater’ thesis) possessed a large collection of them (Bevan 2017: 3).

How has the belief become so widespread?

The ‘Europe as backwater in 1500’ narrative is one that’s pretty far from reality. You can definitely make an argument that China in particular remained more advanced than Europe at this point in several important ways, though not in all. But you can’t make the same claims for any other Asian society. You could also argue that as overall differences across Eurasia at this point remained small, Pomeranz’s ‘world of surprising resemblances’ is the best way to describe things. If you were looking for differences though, the evidence seems to show that the world’s most advanced technologies were found either in Europe or in China, and that the mechanical, nautical and scientific areas where Europe excelled were those that would become increasingly important in the succeeding centuries. You certainly cannot support an argument that Europe was a backwater. So how has the belief become so widespread?

The period from the mid 90s to the mid 2010s was when the “rise of Asia”, and of China in particular, really started to impinge on the Western consciousness. As The Economist put it in 2012, “It is not exactly news that the world's economic centre of gravity is shifting east”, and as the map they included in the article demonstrated, it was not just shifting but returning to the east. This shift was reflected in the academic discourse too: a central strand of California School works like The Great Divergence and Roy Bin Wong’s China Transformed (1997) was to rehabilitate late Ming and Qing dynasty China from the view, dating back to Marx and Weber, that they had been nothing but stagnant oriental despotisms. The idea that Asia, particularly China, had always been the world’s economic centre except for a brief period in the 19th and 20th centuries, became popular.

Concurrently this period saw a change in approach of the tendencies on the left that downplayed or attacked the achievements of Western civilisation. Traditionally this had been done in a Marxist or dependency theory framework where Europe was seen as exploitative, but central (for example Immanuel Wallerstein’s world systems theory or Andre Gunder Frank’s earlier work in dependency theory). The California school though aimed to decentre or provincialise Europe entirely, as we see in its most extreme versions such as Frank’s or Hobson’s work.

The rhetoric of Europe as a backwater also spread into more popular historical works such as the bestselling ones by Niall Ferguson and Peter Frankopan that I mentioned in the introduction, which undoubtedly did more than the less well-known California school ones to influence mainstream discourse. We could add the continuing influence of an older misunderstanding of European history, of the middle ages as a static world of knights, castles, and unchanging agricultural drudgery which was swept away by the dynamic modern era that followed, missing the huge advances that happened over this period.

The intellectual and geopolitical context of the time therefore was ripe for the belief of ‘Europe as a historical backwater’ to become widespread. Like so many intellectual trends, this one grew out of a need to counter a perceived narrative of eurocentrism which many of the authors mentioned (e.g. Pomeranz, Frank and Hobson) considered to be dominant at the time they were writing. But as so often happens, this counternarrative has now become accepted wisdom and itself needs to be corrected.

Bibliography

Adas, M. (1989). Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Cornell University Press.

Allen, R. C. (2009). The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Bevan, P. (2017). The Qianlong Emperor’s English Clocks to China and Back – Baubles, Bells and Booty. Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society vol 81.

Bisin, A., & Federico, G. (Eds.). (2021). The Handbook of Historical Economics. Academic Press.

Broadberry, S., Campbell, B., van Leeuwen, B. (2011). English Medieval Population: Reconciling Time Series and Cross Sectional Evidence. Warwick Department of Economics.

Broadberry, S. (2013). Accounting for the great divergence. LSE Economic History Working Papers No: 184/2013.

Broadberry, S., Guan, H., & Li, D. D. (2018). China, Europe, and the great divergence: a study in historical national accounting, 980–1850. The Journal of Economic History, 78(4), 955-1000.

Broadberry, S. (2021). Historical national accounting and dating the Great Divergence. Journal of Global History, 16(2), 286-293.

Cipolla, C. (1977). Clocks and Culture 1300 - 1700. W. W. Norton & Company

Cipolla, C. (1993). Before the Industrial Revolution. European Society and Economy 1000 – 1700 (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Clark, G. (2009). [Review of Contours of the World Economy, 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History, by Angus Maddison]. Pp. xii, 418. 42.95, paper. The Journal of Economic History, 69(4), 1156-1161.

Comin, D., Easterly, W., & Gong, E. (2010). Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 BC?. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2(3), 65-97.

Deng, K., & O'Brien, P. (2017). How well did facts travel to support protracted debate on the history of the Great Divergence between Western Europe and Imperial China?. LSE Economic History Working Papers No: 257/2017.

Di Cosmo, N. (2001). “European Technology and Manchu Power: Reflections on the ‘Military Revolution’ in Seventeenth-Century China.” In Making Sense of Global History, ed. Sølvi Sogner. Oslo University Press, pp. 119-39

Duchesne, R. (2005). Peer Vries, the Great Divergence, and the California School: Who's In and Who's Out?. World History Connected 2.2 (2005).

Ferguson, N. (2012). Civilization: The West and the Rest. Penguin.

Findlay, R., & O'Rourke, K. H. (2007). Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium.

Frank, A. G. (1998). ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Univ of California Press.

Frankopan, P. (2017). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. Vintage Books.

Goldstone, Jack (2009): Why Europe? The Rise of the West in World History, 1500-1850. New York: The McGraw Hill Companies.

Hobson, J. M. (2004). The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge University Press.

Holt, R. (1988). The Mills of Medieval England. Blackwell.

Jedwab, R., Johnson, N., Koyama, M., (2022). "The Economic Impact of the Black Death" Journal of Economic Literature 60 (1): 132–78.

Jones, E. L. (1987). The European miracle: environments, economies and geopolitics in the history of Europe and Asia. Cambridge University Press.

Landes, D. S. (1999). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. W W Norton & Company.

Landes, D. S. (2000). Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World. (2nd ed). Harvard University Press.

Maddison, A. (2001). The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. OECD.

Maddison, A. (2003). Contours of the World Economy, 1 – 2030 AD. Oxford.

Maddison Project Database version 2023: Bolt, Jutta and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2024), "Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy: A new 2023 update", Journal of Economic Surveys, 1–41.

Needham, J. (1965). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge University Press.

O'Rourke, K. H., & Williamson, J. G. (2002). After Columbus: Explaining Europe's Overseas Trade Boom, 1500–1800. The Journal of Economic History, 62(2), 417-456.

Pomeranz, K. (2001). The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton University Press.

Pomeranz, K. (2011). Ten years after: responses and reconsiderations. Historically Speaking, 12(4), 20-25.

Pomeranz, K. (2017), “The Data We Have vs. the Data We Need: A Comment on the State of the “Divergence” Debate (Part I)”, The NEP-HIS Blog.

Roland, A. (2003). Once More into the Stirrups: Lynn White Jr., Medieval Technology and Social Change. Technology and Culture, 44(3), 574-585.

Terlouw, K. (1998). Review of" ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age" by Andre Gunder-Frank. Journal of World-Systems Research, 178-180.

Tibbetts, G. R. (1981). Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean Before the Coming of the Portuguese, being a translation of Kitab al-Fawa id fi usil al-bahr wa’l-qawa’id, of Ahmad b. Majid al-Najdi. The Royal Asiatic Society.

Vries, P. (2010). The California School and Beyond: How to Study the Great Divergence? History Compass, 8(7), pp.730-751.

White, L. (1974). Medieval Technology and Social Change. Oxford University Press.

Related articles:

Hobson’s claim that Arab navigators sailed around Africa to Europe before Europeans did was interesting so I looked into it. It turns out to be a classic case of misreading of the sources in the service of an argument. Hobson also cites a similar work where it also appears: Before European Hegemony by Janet L. Abu-Lughod. Both she and Hobson trace the claim back to Tibbetts (1981), a translation of the writings of 15th century Arab navigator Ahmad ibn Majid. But if you actually read the relevant passages in Tibbetts’s translation, it’s clear that Ahmad ibn Majid is just describing the state of the geographical knowledge (and speculations) of his day by means of an imaginary voyage around the world, as Tibbetts himself notes on page 396. The relevant section is the ‘Description of the coasts of the world’ from pages 204 - 216. The ‘voyage’ also includes, for example, a journey around the coastline of Siberia from Europe to China. As would be expected from this sort of account, there is no detail about the west coast of Africa until we get to the Sahara, contrary to Abu-Lughod’s claim that the voyage is “described in such detail in the manuals that one cannot doubt the prior circumnavigation of Africa by Arab/Persian sailors” (Hobson 2004: 138).

This is great, a deep dive into why (as I like to remind people) Britain wasn't strong because of the empire but had an empire because it was strong.

That's a really good post. I often think that a lot of economic historians really downplay how much of an economic jump the industrial revolution was.

I don't think it helps that history tends to be a subject studied by humanities students. Stories about politics, generals, battles and kings tend to be the bread and butter. There is little interest and almost no practical knowledge about industry, technology and manufacturing.

I would add to your list of folk beliefs the idea that invention and technological progress comes from science and the university system. Whereas in practice almost all of the new technology and progress came about in workshops with boys that worked as apprentices since their early teens. People like Whitworth, Maudslay, Aspdin, Wilkinson, etc are almost unknown by the general public yet are far more responsible for the world we live in today than say Newton, Einstein or Napoleon.