The rebirth of Anglo-America?

The true level of British ancestry in the US census compared with genetic studies. How the ‘nation of immigrants’ came to be, and the status of Anglo (or heritage) America.

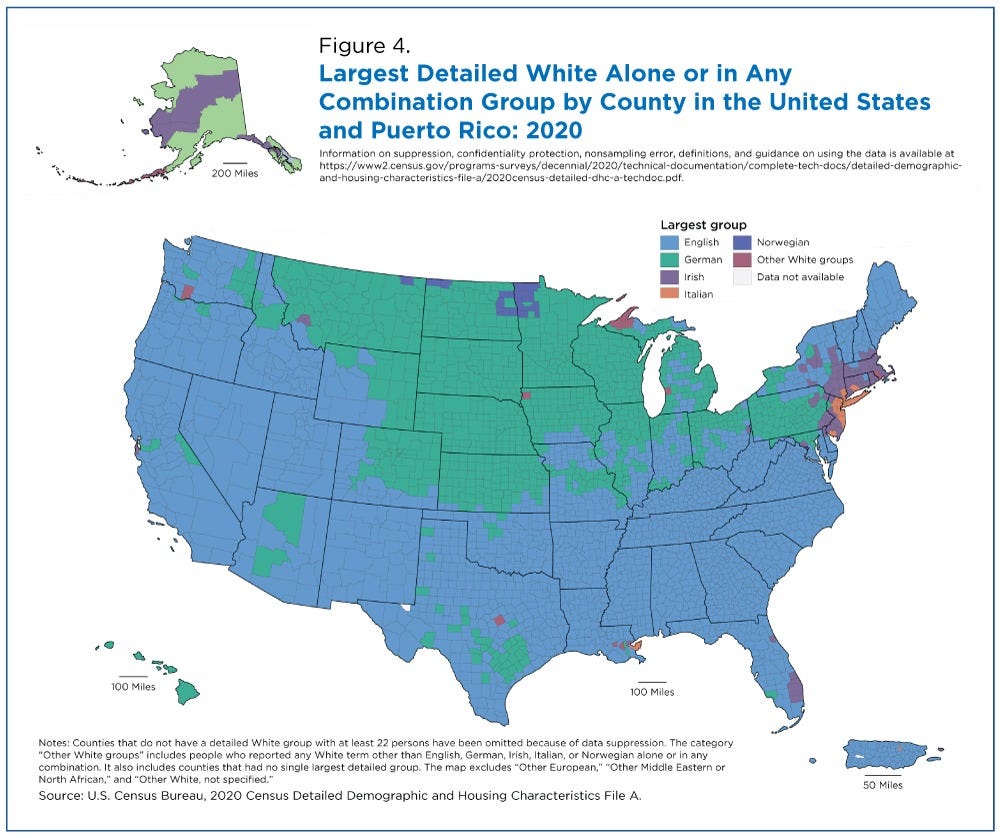

Recently I saw Ed West had identified an apparent rise in English-American identification in the US. The map triggering this discussion was unsourced but the one below from the US Census Bureau shows substantially the same story: in the 2020 census English was the largest white ancestry across much of the country, and the most common ancestry overall.

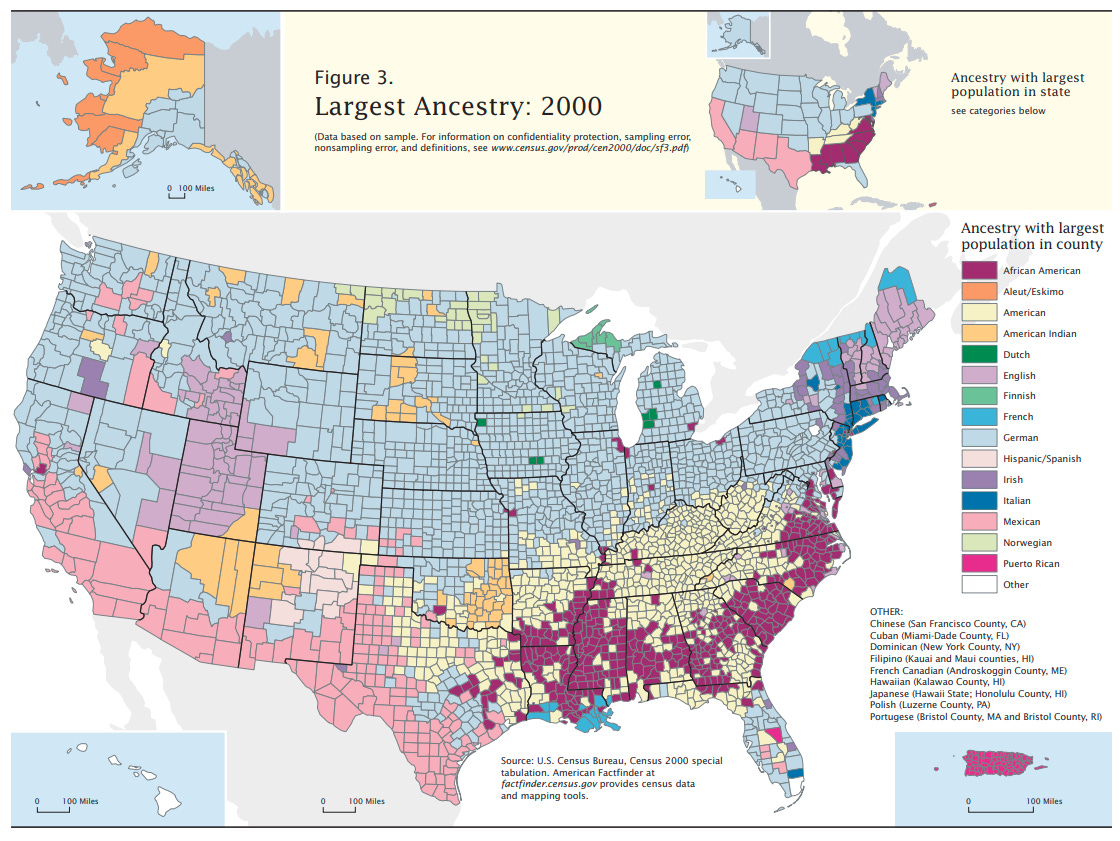

I certainly found this surprising when I first saw it, considering that the stereotypical white American identifies their ancestry as something like Irish or German, but never English. This also marked a significant change from previous censuses: in the 2000 census German was by far the largest white ancestry (42.8 million), with English fourth (24.5 million) after Irish and African American. The British total would also include Scotch-Irish1 (4.3 million), Scottish (4.9 million), Welsh (1.8 million) and British2 (1.1 million), but at 36.6 million, this was still less than the German total. This widely disseminated map of the 2000 census shows English ancestry predominant only in Utah and parts of New England.

People have offered a few speculative explanations for this change. One is that it is merely a statistical artifact, with the level of English ancestry identification depending on whether the respondents answer ‘American’ or not, as ‘American’ ancestry generally means old stock British origins. Another is that the rise of ancestry DNA tests have disproved family myths about ‘ethnic’ ancestors and shown that their ancestry is actually substantially British. Another is that there is a resurgent racial/Anglo consciousness, or that identifying as ‘not English’ was a boomer fad of the 90s and 2000s.

With the current fight over the resurgent idea of heritage Americans, this is a timely question. This article will look into possible explanations, try and get a better sense of the true level of British ancestry, and go into the history of how the US’s self conception changed from ‘distilled Anglo-Saxons’ to a ‘nation of immigrants’ in the 20th century.

Article subsections

British ancestry in the US census over time

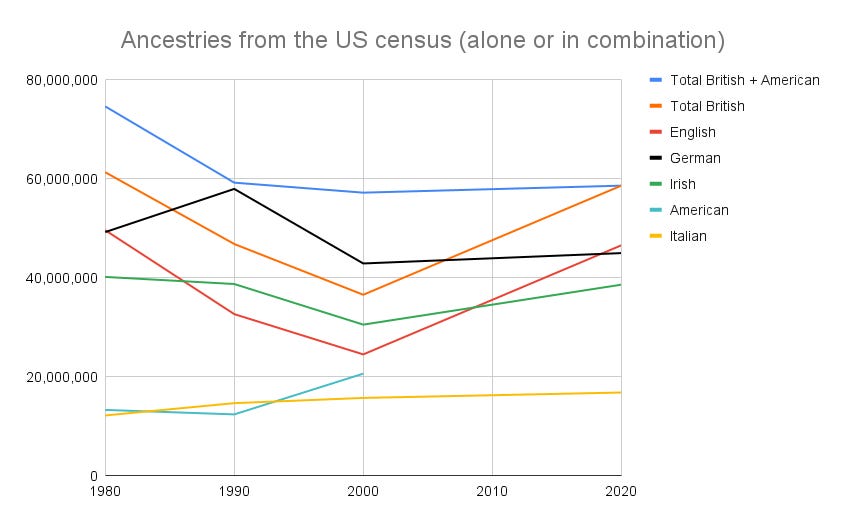

This chart shows ancestries (alone or in combination) from the US census in 19803, 1990, 2000 and 20204. In addition to the original figures, I’ve added all the British ancestries (English, British, Scots-Irish, Scottish, Welsh) together into a ‘Total British’ category, and then added ‘American’ to this to make a ‘Total British and American’ category. (Those who put their ancestry as ‘American’ tend to be of British ancestry). Raw data is here.

There was a large drop in people claiming English and British ancestry in 1990 and 2000, but a return to the 1980 level in 2020. However, if we look at total British and American ancestry, then we see a drop between 1980 and 1990, but subsequently the numbers are pretty stable. I’ll go into more detail on this imminently, but the short explanation is that in 1990 and 2000 English was not offered as an example ancestry on the census form, while in 2020 it was (under a changed ‘race’ box), and thus the ‘statistical artifact’ explanation explains most of the change.

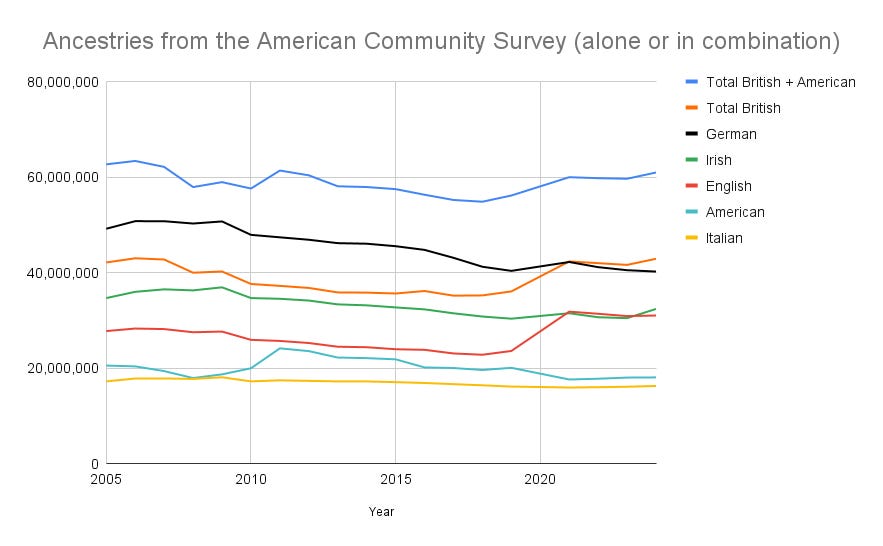

Since 2005, ancestry data has been collected by the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) instead of in the census. This data tells a similar story (source data). English and British ancestry slowly declines from 2005 until 2019, then jumps in 2020. There has also been a sharp rise in overall British ancestry in 2024, though this is driven almost entirely by over a million more people identifying as having Scottish ancestry. I’ve got no idea what the cause of this is, you could speculate that it’s due to Trump’s Scottish ancestry, though there was no comparable rise in 2016, and Irish also saw a big jump.

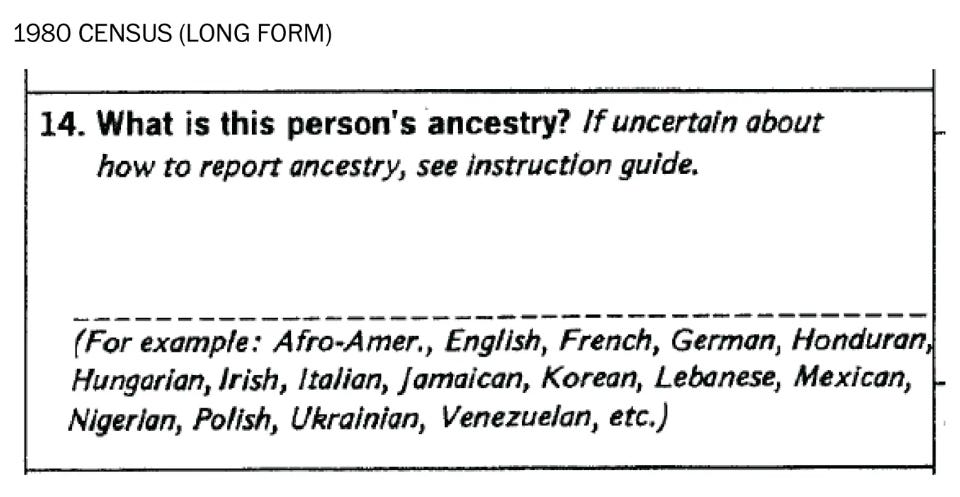

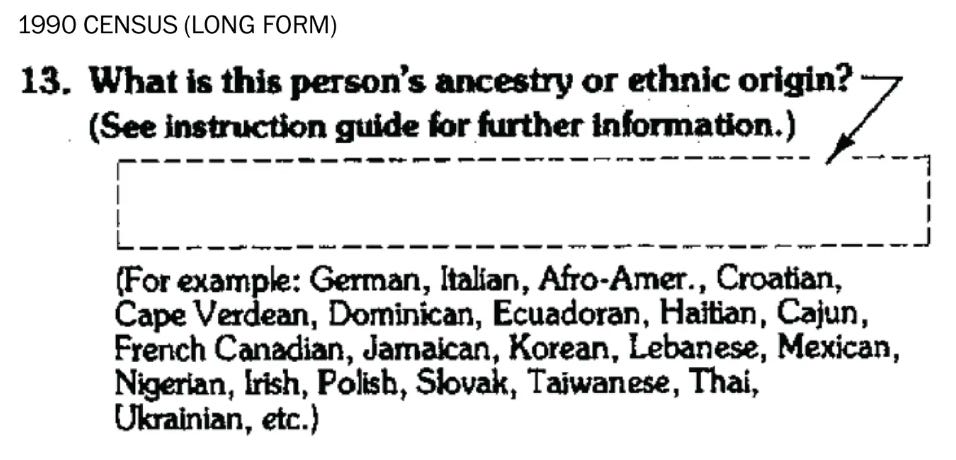

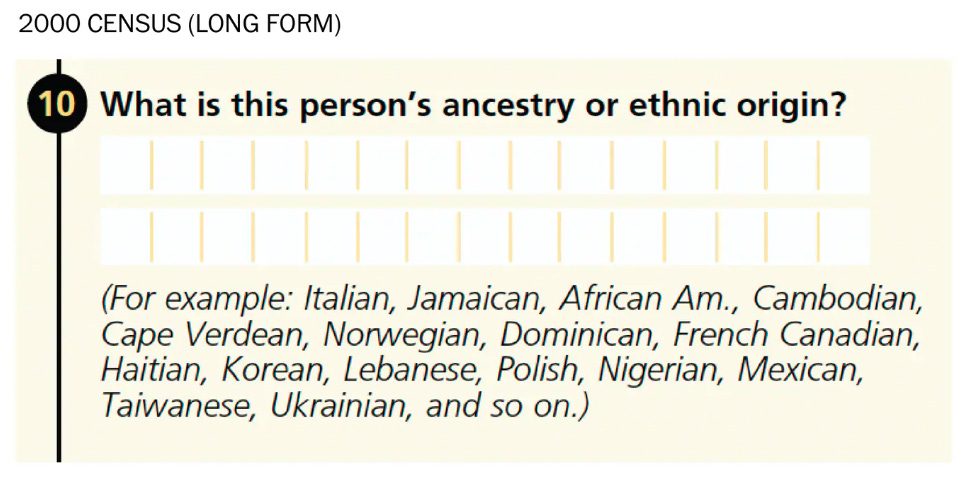

The changing wording of the census and ACS questions are what has driven apparent rises and falls in ancestry numbers. This Washington Post article (archived version) goes into more detail and includes the exact wording, which I’ve reproduced below.

In the 1980 census, English, together with German, Irish, Italian and various others, was listed as an example ancestry, and as you can see from the first chart above, English ranks highly in responses.

On the 1990 census English was dropped as an example, but German and Irish remained (with German first), and the results reflect this, with a large drop in English, a large rise in German and roughly stable Irish.

In 2000, German and Irish were also dropped, and they then continued to decline as English did. Italian stayed on the list and continued to rise.

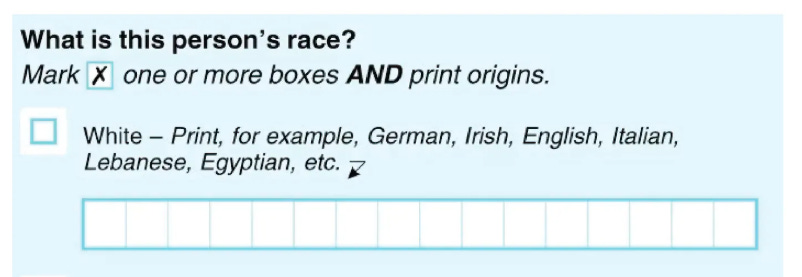

Since 2000 the ancestry question has been dropped from the census and transferred to the ACS. However from 2020 both the census and the ACS changed the ‘race’ question, which had previously not allowed any more detail than ‘white’, to include a write-in box for racial ancestry, with the top three example white ancestries being German, Irish and English.

It’s certainly possible that increased ancestry DNA testing or social trends explain some of the increased English ancestry identification in 2020, but clearly the main factor is this changed prompt. However, it is notable that English ancestry seems to be affected more by it being listed as an example than other ancestries are. In 2020, English, German and Irish were all added as example ancestries, having been absent since 1990, but German and Irish saw a much smaller uptick than English did. This would fit with the idea that English ancestry is more latent than others, and people are less likely to identify it unless they are prompted.

So what can we say from this about the real levels of British ancestry in the US population? Going by this data, including American ancestry, around 60 million white Americans have full or partial British ancestry: around 30% of the roughly 190 million non-Hispanic white Americans, or 18% of the total population. This is about 50% higher than German, the next largest ancestry at 40 million. Clearly though these questions of ancestry are highly malleable, so next I’ll look at what genetic and historical studies say about the proportions.

Genetic studies on US European ancestry

Unfortunately the genetic clusters used by most studies are too broad to answer the question. For example this recent paper was identified by Lyman Stone as showing levels of British ancestry of 85% in the US white population. However, as others (and he) subsequently clarified, the ‘British’ cluster here really just means northwestern European, so it doesn’t tell us much.

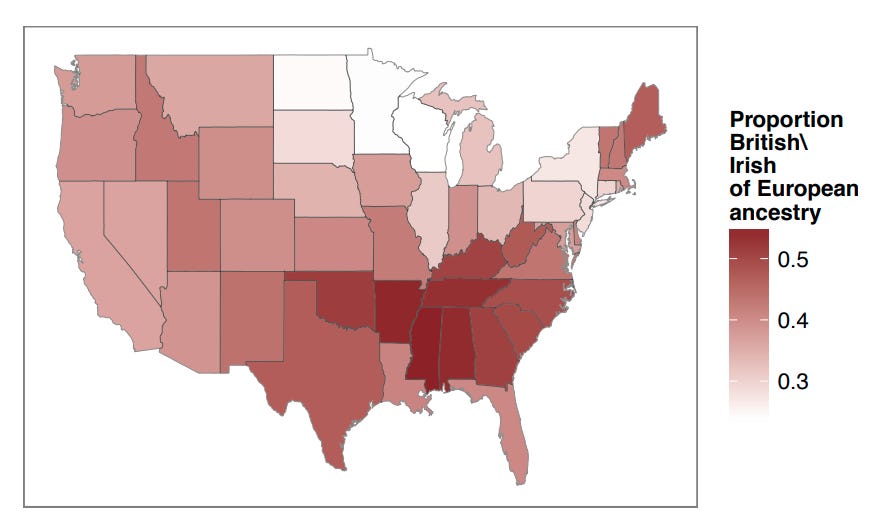

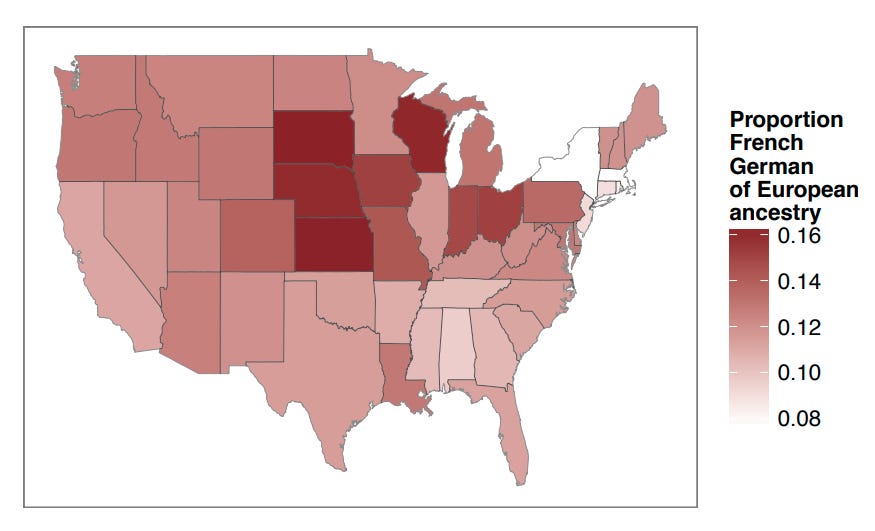

The only study I’m aware of that does shed more light on the question is the 2015 paper The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States, based on 23andMe data. 23andMe breaks down ancestry into categories including ‘British / Irish’ and ‘French / German’, which is not ideal for isolating British specifically, but is still more useful than other papers I’ve found. Figure S10 in the paper shows the relative proportions of different European ancestries per state, from which we can see that the British/Irish proportion (25% to 40% for most states) is multiple times greater than the French/German one (8% to 16%).

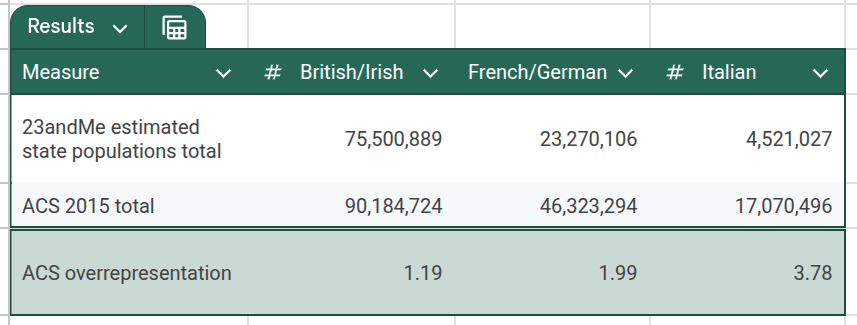

Kasia Bryc, one of the authors of this paper, has made the source data available on her website. I combined it with the non-Hispanic white populations of each state from the 2010 census to arrive at an estimate of the proportion of each ancestry in the US non-Hispanic white population. The results for three of the groups are in the table below (full data here). I’ve included the estimated ancestry numbers based on the 23andMe study numbers, the ACS numbers from that year, and the proportion by which the ACS numbers are greater than the 23andMe numbers.

The resulting numbers from the 23andMe ancestry percentages plus state populations are smaller than the ACS numbers in all cases, and they should not be taken as an accurate guide to total numbers. The total percentages of all ancestry groups only ever add up to around 70% despite all major groups being present, and to take one example, they only result in 4.5 million of Italian ancestry, less than the 5.1 million Italian immigrants to the US over its history. 23andMe customers are also, of course, not a representative sample, though I would not expect significant differences between the European ancestry groups I am interested in here as they have similar income levels.

What is useful is the relative difference between groups. While British/Irish ancestry is 1.2x more prevalent in the ACS than in the genetic data, French/German ancestry is 2x more prevalent, and Italian ancestry is 3.8x as prevalent. I will assume that it is British, rather than Irish, ancestry which is undercounted in the ACS, due to it being a less salient and desirable one. Going by this data then, the census/ACS proportions of only 1.5x British vs the next highest ancestry of German is a significant undercount, and there are likely tens of millions more Americans of British ancestry than show up in the census or ACS data.5

These results fit with the idea that people are more likely to choose more desirable and salient identities. In Mary Waters’ study of the way that Americans chose their ethnicities in 1990, she found that Italian was the most common response to the question, “If you could be a member of any ethnic group you wanted, which one would you choose?”, on the grounds that Italians had a warm family life and excellent food. Italian was also the ancestry most likely to be chosen for children of mixed marriages (Waters 1990: 142-143).

As for the question of whether ancestry tests like this made a different to people’s self conception, it seems plausible, but I haven’t found any studies on it.

What can we tell from US immigration history?

So, genetic data indicates that British ancestry is significantly more prevalent than is reported in census data. What does the demographic and immigration history of the US tell us?

Before the 1830s there had been little non-British immigration to the US, and the population was growing fast almost entirely though natural increase. On the eve of the revolution the white population was 60% English and 80% British (Kaufmann 2004: 13), and in the decades afterwards immigration levels were very low (Kaufmann 2004: 20). The white population more than trebled from 2.2 million to 7.9 million over the forty years from 1780 to 1820 (the fertility rate was 6.3 in 1820). Going by the British percentage in 1776, this would have meant around 6.4 million Americans of British ancestry by 1820. Immigration then began to pick up, though slowly at first: only 750,000 came between 1820 and 1840, (going by the numbers in Dinnerstein 2009) by which time the white population had nearly doubled to 14.2 million, so we could estimate at least 11 million of British ancestry in 1840.

From 1840 until the late 1920s the US saw large amounts of immigration from elsewhere in Europe. The total numbers of European immigrants (from 1820 until 1995) were around 38 million (Dinnerstein 2009), with the largest non-British sources being Germany at 7.1 million, Italy at 5.4 million and Ireland at 4.8 million. However Britain still remained the third largest source, at 5.1 million. (This is quite a good visualisation of total immigrant flows).

Considering the estimated 11 million white Americans of British ancestry in 1840, their high fertility rates, and the subsequent 5.1 million British immigrants, it seems unlikely that ancestry for any other European-descended population today could approach much more than half of the British one. We do have studies finding that immigrant fertility rates were higher than native ones, but the differences largely evened out by the second generation (Hacker et al 2019). I’m not going to attempt the calculations that take into account year of arrival and fertility rates, though I’d be interested in seeing any attempts at this.

The 1920 National Origins immigration formula (Senate Report 81-1515 of 1950, p. 886) estimated British ancestry at 39.2 million (41% of the white population), with German at 15.5 million (16%) and Irish at 10.6 million (11%). This is more in line with the immigration history and the genetic studies than with more recent census data which shows a British descended population of only 1.5x the German numbers. Considering that post-1920 immigrant flows are unlikely to have much effect on the composition of the US white population due to the small numbers relative to the existing population, we can say that this too supports the view that British ancestry is significantly undercounted today.

The transformation of American identity into ‘a nation of immigrants’ in the 20th century

So what’s the explanation for this undercount? One of the most interesting books I’ve ever read is Eric Kaufmann’s The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America, which I’ve referred to several times in this article . It’s quite hard to acquire but he’s made it freely available here. It details how mainstream American self-conception shifted over the 20th century, from one defined by its Anglo-protestant identity to ‘a nation of immigrants’.

When I first read this it made me realise how much my own ideas of what America was (which was certainly, at the time, uncomplicatedly that of ‘a nation of immigrants’) had been formed by the films and TV I’d consumed growing up in the 1990s and 2000s. One I remember in particular was the 1986 children’s cartoon An American Tail. This was a retelling of the Jewish immigrants who had migrated from the Russian empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Jews are represented as mice fleeing the Cossacks (menacing cats), to America, the land where ‘there are no cats, and the streets are paved with cheese’. Re-watching these clips now, all the references are clearly based on the Jewish experience, but this is never explicitly mentioned and, as can be seen by its title, the film is conceived of as a general American narrative. There was also, of course, Disney’s Pocahontas in 1994, though this added to the impression, as it hardly portrayed the English settlers in a very positive light. Probably the most prominent symbol of America in my mind at the time was the Statue of Liberty, which I had understood solely in its recast ‘huddled masses yearning to breathe free’ form rather than its original message of political liberty.

As Kaufmann’s book sets out, until the late 19th century the American self-conception was of an Anglo-protestant people whose political liberties were traced back to the Anglo-Saxons. Only in America had they fully thrown off the Norman yoke and thus become distilled and superior Englishmen. You can see this throughout the pre- and post-revolutionary period, in the 19th century and into the 20th. In 1776 Thomas Jefferson spoke of “Hengist and Horsa, the Saxon chiefs from whom we claim the honour of being descended, and whose political principles and form of government we have assumed.” In 1889 Theodore Roosevelt situated the winning of America’s wars as “a work that began with the conquest of Britain, that entered on its second and wider period after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, that culminated in the marvelous growth of the United States” (Kaufmann 2004: 17-18).

Immigrants could become American, but this Americanisation process meant adopting Anglo-Saxon identity. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “the representatives of many old-world races are being fused together into a new type”, one that was “shaped from 1776 to 1789, and our nationality was definitely fixed in all its essentials by the men of Washington’s day” (Kaufmann 2004: 30).

From the last years of the 19th century Anglo-Saxonism began to lose prominence. Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis held that the experience of the frontier, not English origins, was central to American identity: “in the crucible of the frontier the immigrants were Americanized, liberated, and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics.” (Kaufmann 2004: 51). But Turner was still an assimilationist who worried about the cultural impact of new immigrants: this was a long way from ‘a nation of immigrants’ or the subsequent cosmopolitanism.

From this period onwards various influential activists and intellectuals started constructing an alternative, cosmopolitan vision of American identity, one where Anglo-Saxonism and the settler experience would be banished so that a universal nation could take its place. The late 19th/early 20th century Columbia professor and social reformer Felix Adler sought to recast the mission of Reform Judaism into a universal one whereby eventually all ethnicities, including his own, would dissolve into a universal one (Kaufmann 2004: 91). Jane Addams and others in the settlement movement working to alleviate poverty in immigrant dominated cities, spoke repeatedly of the need to downplay Anglo-Saxonism in favour of a more cosmopolitan standard (Kaufmann 2004: 99). The melting pot term was popularised by Israel Zangwill’s 1908 play The Melting Pot (1908), in which the protagonist looks forward to ethnic divisions melting away. Philosopher Horace Kallen attacked Anglo-Saxonism and assimilationism and advocated cultural pluralism in articles such as ‘Democracy Versus the Melting Pot’ (1915).

Prominent early-20th century scholar John Dewey also sought to downplay Anglo-Saxonism but was more skeptical of cultural pluralism. In a letter to Kallen, Dewey expressed his approval of his ‘Melting Pot’ essay. ‘I quite agree with your orchestration idea’, Dewey explained, ‘but upon condition we really get a symphony and not a lot of different instruments playing simultaneously. I never did care for the melting pot metaphor, but genuine assimilation to one another—not to Anglo-saxondom—seems to be essential to an America’ (Fallace 2012).

It was writer Randolph Bourne who most fully articulated what became today’s asymmetrical multiculturalism in his article Transnational America, published in The Atlantic in 1916. Bourne wrote that the time had come to assert a higher ideal than the melting pot, that Anglo Americans should give up their search for a native American culture, and embrace cosmopolitanism, which should be protected: “[w]hat we emphatically do not want is that these distinctive qualities should be washed out into a tasteless, colorless fluid of uniformity.”

These intellectual movements were made up of liberal Anglo-Protestants and the descendants of recent Jewish immigrants. Both groups sought to escape the strictures of their own ethnic backgrounds and were attracted to universalism, trends which Kaufmann describes as expressive individualism and cultural egalitarianism. The Jewish ones also likely additionally resented Anglo-Saxon predominance in particular. A few decades later, the Jewish predominance became more marked with the rise of the group known as the New York Intellectuals, which came to dominate American intellectual life in the mid 20th century.

The early 20th century also saw a rise in cosmopolitan rhetoric from more mainstream Anglo-protestant institutions such as protestant churches, but neither these nor left-wing intellectuals were enough to change a nation’s culture on their own. On the whole, Anglo-Protestantism was still in control, as seen in the passing of the 1924 Immigration Act which intended to maintain America’s ethnic balance, even if it was becoming less predominant in elite circles.

In the 30s and 40s, universalist and cosmopolitan ideals began to be taken up among more mainstream segments of the population. Danish origin historian Marcus Lee Hansen wrote an influential immigrant-centered version of American identity in the late 1930s. In 1943 Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie published One World, which became a record-breaking bestseller. He wrote “Our nation is composed of no one race, faith, or cultural heritage … They are linked together by their confidence in our democratic institutions … Minorities are rich assets of a democracy” (Kaufmann 2004: 178).

Meanwhile the increasingly influential New York intellectuals continued to develop progressive ideas into a vision of liberal cosmopolitanism intended to displace the traditional Anglo-American identity. One example was the attack by Marxist critics at Partisan Review (such as Clement Greenberg and latterly Dwight Macdonald) against American art movements like regionalism6 in favour of a radical, European avant-garde tradition.

In the decades during and after the second world war, mainstream American opinion and institutions switched wholesale to the new idea of America’s identity. The immigrant-centered interpretation of the Statue of Liberty and the ‘melting pot’ became standard in school textbooks. In 1952 Truman, attempting to liberalise America’s immigration policy, attacked immigration restrictionism on ethnic grounds as unworthy of American ideals, invoking Emma Lazarus’s ‘huddled masses’ poem as well as the ‘neither Jew nor Greek’ biblical passage (Kaufmann 2004: 183).

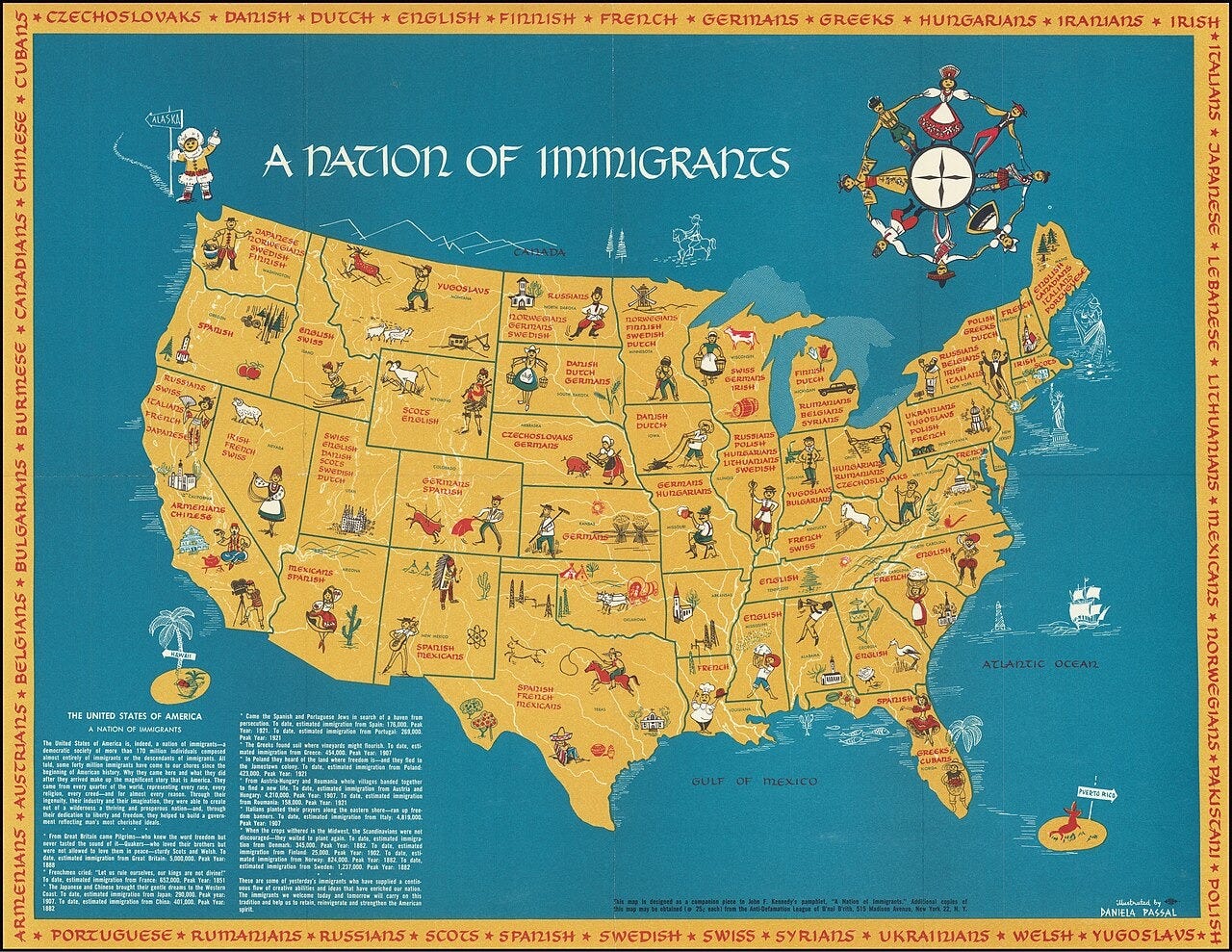

The symbolic triumph of this movement was the election of the first Catholic president John F. Kennedy in 1961, who had published, with the ADL, the book A Nation of Immigrants in 1958. You can see in this map that accompanied it the downplaying of British ancestry that continues to this day (see the French in South Carolina and the Swiss in Kentucky).

Subsequently America saw the various civil rights acts, the 1965 immigration act which ended the policy of maintaining America’s historic ethnic identity, and then the whole post 60s cultural transformation towards valorising non-Anglo cultures, the more exotic the better, and towards asymmetrical multiculturalism.

Of course, by the 20th century, America was to a significant extent a nation of immigrants, and the descendants of Irish, German, Jewish etc immigrants would have increasingly entered into elite institutions even had the national culture not become pluralist. But this does not mean that the cultural change itself was inevitable. Many other dominant ethnicities fight to maintain cultural hegemony even in the face of large ethnically different populations, as in Iran, Dubai, Israel, Burma, Estonia or Russia.

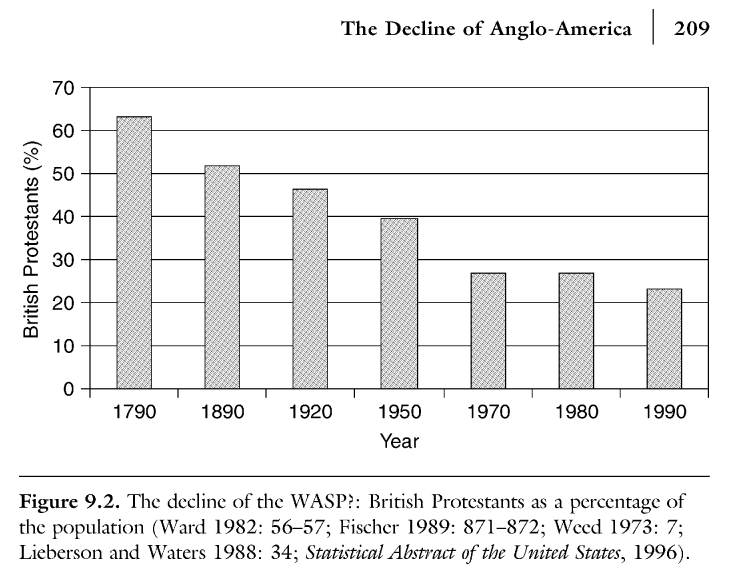

This is what explains the sharp drop in Anglo-Protestant identification between 1950 and 1970, as can be seen in this chart from Kaufmann’s book. Considering this was a time of relatively low immigration compared to previous or subsequent periods, this drop can be put at the feet of this cultural transformation. To many people it seems unremarkable that today Western countries valorise the exotic and the marginal, but this valorisation is in fact deeply odd historically speaking, and stems from these early 20th century intellectual trends finding fertile ground in the society of 20th century America and the West more widely.

In conclusion

So to wrap up, the apparent rise in British ancestry in the census and ACS is indeed predominantly a statistical artifact. I would not discount the effect of genetic ancestry testing, or of political changes making heritage Americanism more salient, but I can’t prove them. However more generally, genetic and historical studies indicate that British ancestry in the US population was substantially undercounted both before and after the changes in the census and the ACS. I haven’t come up with numbers for how much in this article, but going by what I’ve found out I’d estimate the true numbers are at least 30% higher than the 60 million British ancestry count from the 2020 census.

So what of the future? A revival of explicit Anglo-Saxonism today is unlikely. I can’t see a return to the America of the 19th century that you can see in an issue of the popular Anglo-Saxonist Century Magazine from the 1890s, dedicating a large amount of column inches to subjects like ‘By the Waters of Chesapeake’, ‘Drowsy Kent’ or ‘A Summer Month in a Welsh Village’. However, the recent prominence of the idea of ‘heritage Americans’ shows that the fight to maintain an American identity that reaches beyond the cosmopolitan and outgroup-biased ‘nation of immigrants’ persists.

Data

Data for charts is here.

Bibliography

Bryc, K. et al. (2015). The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. The American Journal of Human Genetics, Volume 96, Issue 1, 37 - 53.

Dinnerstein, L. (2009). Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration. Columbia University Press. Appendix.

Fallace, T. (2012). Race, Culture, and Pluralism: The Evolution of Dewey’s Vision for a Democratic Curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(1), 13-35.

Hacker, JD., Roberts, E. (2019). Fertility decline in the United States, 1850-1930: New Evidence from Complete-Count Datasets. Ann Demogr Hist (Paris). 2019 Jun;138(2):143-177.

Kaufmann, E. (2004). The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America. Harvard University Press.

Lissak, R. S. (1989). Pluralism and Progressives: Hull House and the New Immigrants, 1890-1919. University of Chicago Press.

Senate Report 81-1515 of 1950.

Van Dam, A. (2024, December 6). What’s America’s largest ethnic group, and why did we get it wrong for so long?. The Washington Post. Archive.

Waters, M. C. (1990). Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America. University of California Press.

Related Articles

Scots-Irish should properly be counted as British not Irish as when they emigrated to the future US they were recent settlers in Ireland from Scotland or northern England.

Those marking ‘British’ ancestry may be more recent immigrants.

It’s interesting that the ancestry question was first added in the 1980 census at the urging of ethnic organisations who wanted to count their ‘members’ better. The census bureau resisted it for being imprecise (Waters 1990: 10).

The question was not asked in the 2010 census.

Or, of course, fewer Germans, but I think the total 23andMe numbers are themselves an undercount, as you can see by the Italian example I gave.

A style recently recently repopularised by the Department of Homeland Security’s twitter account.

Those of us who might find an appeal in a revival of Anglo-Saxon identity will be put off by the extent to which England itself has abandoned it. Even pride in having a nation founded in Enlightenment ideals is like ashes when you see what has become of the nations that birthed the Enlightenment.

A fascinating read - thank you.