Notes on China’s alternative modernity

Mostly impressive, sometimes eerie. Surface order, with an undercurrent of chaos.

I recently spent some time in China, visiting Chongqing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong and Macau. There’s lots of interesting things I could say about this trip, but in this article I’m going to focus specifically on the unique sense of ‘alternative modernity’ you get when travelling in China, from things like the cities, cars, trains, and the way phones are used. You could say that this sense is not limited to China and that Japan, Taiwan and Korea offer a similar experience, but given that they’re a relatively small part of the, for now, US-led order, they’re not really a truly alternative pole like China is.

The three times I’d visited China previously had all been between 2008 and 2010, and then, even in the major cities, it very much felt like a country that was still in the process of being built, and where the sense of alternative modernity that I noticed this time wasn’t really present. There were no Chinese EVs on the roads and more foreign cars, payments were made in cash rather than with WeChat and Alipay, and there was little high speed rail (I took a night train for the 750 mile journey from Shanghai to Beijing, a journey that can now be done via HSR in four and a half hours). On this visit though the country substantially felt like it had been built, and the way in which this had been achieved made it feel more alien despite it being more modern.

I’ll mostly be drawing on experiences of the mainland – Hong Kong and Macau, naturally, feel different. Additionally, the places we visited are the wealthier parts, so this isn’t intended to be a comprehensive overview of the country as a whole, just some impressions of its cutting edge.

Cities

The cities we went to had clearly had a lot of care and attention put into them to make them pleasant and safe environments. The streets, metros and parks were clean and well cared for, and despite the busy roads, the environment was pretty walkable, with a lot of pedestrian crossings and overpasses. One notable thing was how prevalent public toilets were compared to London, where in my experience, they are more likely to have been converted into underground bars called things like Ladies & Gentlemen or WC Wine & Charcuterie. A small but significant measure of public goods provision.

One of the main things I wanted to see in China was the skyscraper light shows, and I wasn’t disappointed – every city we visited had one, and they were amazing. Pictures don’t do them true justice, so here’s footage of the Shenzhen one, or see this article for more about them – they are indeed a triumph.

Chongqing, additionally, had a saturday night drone show, which was technically incredible, though I think artistically rather lacking. It was though, another good example of being able to see an alternative modernity, in that the things being celebrated, like Chinese cars and the police, showed some very different societal values from London’s New Years Eve one of sport, music, diversity, and cups of tea.

Outside of the city centres, everywhere was somewhere along the scale from, at best, a 21st century ‘gleaming new malls’ environment to, at worst, 20th-century soviet style apartment blocks. Nowhere we went to seemed run down, even in random suburbs or smaller towns – the most common environment was a Drukpa Kunley style basically fine collection of medium sized apartment blocks and malls.

Something many people note about China is the lack of a historic built environment, which we found to be true, even in cities with a long history like Guangzhou. The only exceptions were a small number of historic sites preserved for tourists, or Disneyland-like reconstructions of old neighbourhoods like Chongqing’s Shibati or Guangzhou’s Yongqing Fang. This tendency is not unique to China, there is a historic East Asian tendency to build in wood and to rebuild often, but it’s still odd to be walking around cities in one of the world’s oldest civilisations and seemingly encountering barely any buildings built before 1970. European colonial ones, such as on Shamian island in Guangzhou, are the exceptions that prove the rule.

The city centres have a seemingly bizarre amount of security. You have to get your bag scanned at every metro station and at various public spaces, such as in order to cross the Haixin pedestrian bridge over the river in Guangzhou. Many public places had large concentrations of police, sometimes with military-style vehicles, that gave a sense of a society teetering on the edge of civil conflict, which is odd given the apparently placid nature of the crowds. You could often look down on a crowd of people and see the flashing epaulettes of security guards or police weaving their way among them.

This made me think about what level of increased security I’d actually want in Britain in order to stop petty crime like phone snatching. I would certainly want more than we have, but I don’t think I’d go as far as to require bag scans at every tube station. As far as I can tell, China had three train station stabbing attacks in 2014 that could conceivably have been prevented by these measures, but none since then. More recently there has been a rise in vehicle ramming attacks instead, and we saw a lot of bollards that have supposedly been installed to prevent these. It shows the mimetic nature of these types of crime around the world – it’s not only Islamic terrorism.

The ‘China as authoritarian society’ meme though has its limits; you also see many examples of where policing doesn’t have much effect and things feel quite chaotic. As I’ll talk about more in the next section, public transport has ubiquitous smartphone loudspeaker slop, despite all the signs forbidding it. People seemed to be unable to wait for passengers to get off a metro carriage before getting on themselves, also in violation of the announcements urging them to wait, and in Guangzhou at least, electric scooters were constantly terrorising pedestrians on pavements.

Guangzhou and Shenzhen

The homogeneity and newness of the built environment can make a lot of Chinese cities look pretty physically similar. This definitely applied to Guangzhou and Shenzhen, even though the former is very old and the latter very new. They both seemed, unsurprisingly, very modern and prosperous, with a weird sense of being made up of a kind of aristocracy of young professionals living above a class of older people doing menial jobs.

An exception was the area around Xiaobei station in Guangzhou. This is known as an African/middle eastern district, so much so that the beggars (the only beggars we saw in China, who looked like they might have been Uighurs) addressed us with Salaam Aleikum as they asked for money via QR code. Even here though, Chinese people were still doing most of the jobs, the Africans and middle easterners are there as traders, not workers. Xiaobei is thus more like what diversity would have looked like in a medieval city than a modern Western one.

Chongqing

Chongqing was more interesting physically, with its multilevel urban environment at the confluence of the Yangtze and the Jialing rivers. This is why it’s recently become Instagram and YouTube-famous, and I half expected the city to be full of Western influencers, but apart from at the influencers’ favourite plaza, this was not the case. In fact, we saw very few non-Chinese, or non East-Asians, in Chongqing or anywhere else, bar Hong Kong or Xiaobei.

Chongqing was the capital during much of the second world war after Japan had conquered the coastal regions, and the museum complex built at the site of Chiang Kai-Shek’s hilltop residence was keen to emphasise that the world’s wartime anti-facist capitals had been Washington, London, Moscow and Chongqing. It’s definitely true that the China theatre of WW2 is pretty unknown in the West, apart perhaps from the rape of Nanking, so it was interesting to learn more about the Japanese land and air campaigns in China. You can see the reason behind the persisting anti-Japanese feeling in China as well as why this is met with incomprehension in the rest of the world. Chinese WW2 history will emphasise the suffering caused by Japanese campaigns there and the bitter resistance, while the rest of the world will remember mainly that Japan was nuked in 1945 and since then has mainly made great cars and anime.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong, of course, felt less Chinese (or at least less PRC Chinese) and more international than the mainland cities, although it still surprised me how Chinese it was. I think I’d subconsciously expected it to have contemporary London’s levels of diversity, when really it was more like London in 1975 (90% Chinese). Still though, the higher levels of English, ability to use credit cards, and lack of an overwhelming police presence made it feel very different to the mainland cities. It’s still a great place though I’d have loved to have visited it in the 1980s when it must have felt truly unique. Now its cityscape, while very impressive, doesn’t seem that different from what you find on the mainland. As with the mainland cities, little of its architectural heritage has been preserved, and colonial era buildings are a rare sight.

Macau

Macau was a bizarre place. We visited on New Year’s day, a public holiday in China, so it was absolutely packed with Chinese tourists taking pictures of each other in hanfu (more about this in the phones section). The city is basically lots of casinos on the seafront, a few old Portuguese buildings, and a lot of somewhat run-down apartment blocks in the city proper. Macau supposedly has a GDP per capita of $76,000, the 8th highest in the world, but you wouldn’t know it from walking around the streets. Presumably the gambling money doesn’t stay locally.

Phones

China is by far the most smartphone-possessed society I’ve ever experienced. The most commonly remarked upon aspect of this is payments, as cards are rarely accepted and the default method is to use the ‘master apps’ of Alipay or WeChat to pay for everything. Cash is still accepted in most places, but it clearly wasn’t the preferred option and I never saw a Chinese person using it. Personally I found the Chinese system less convenient than just using a credit card, even after I’d got used to it, and it was annoying to be made completely dependent on your phone. But it’s certainly interesting as an example of how a society has developed a different payments system, seemingly going straight from cash to phones without cards as an intermediate step. As an aside, one other effect of the decline of cash compared to my previous visits was that it made the figure of Mao loom less large, as his image is present on every denomination of bank note, but is rarely seen elsewhere.

A more negative aspect of phones in China is that it is even worse than Britain for loudspeaker slop on public transport. Every single train and metro carriage had multiple people, from all age groups, blasting out short videos, or carrying out voice note conversations, often with the characteristic slack-jawed scrolling face that characterises the post-2020 world. I’ve heard a theory that China only allows TikTok overseas in order to weaken the West through distraction, while its own domestic version serves educational content. I can say definitively that this is not the case, or if it is the case, it has failed, as based on what I saw, no one has been more one-shotted by short video apps than the Chinese.

The content that people were watching appeared to be the same sort of thing as they watch on TikTok here: celebrities, soft porn, food, face-close-to-the-camera rants, and in one case, an AI generated video of the British royal family, which together with the various Harry Potter themed things we saw, was the only display of our soft power in evidence. The restrictions that do exist seem to be only for under 18s, though on one occasion we saw a little girl, sitting quite happily on the metro without a phone, being offered one by her grandfather, seemingly worried that she didn’t have anything to distract her.

There were frequent signs and announcements telling people not to play sound from their phones, but these were resolutely ignored and I never saw anyone being asked to stop. The CCP can achieve a lot, but they’re clearly powerless against the power of the scroll, a struggle unfortunately made more difficult by the excellent mobile signal everywhere from the metros of every city to most parts of the high speed rail network we travelled on. Britain’s poor mobile signal on public transport does have a few blessings.

Another phone thing in evidence was that every possible photo spot was full of dutiful instagram boyfriends (or whatever the local equivalent is) trying to capture the right shot of their girlfriends, after which it was inspected and redone if necessary. This phenomenon is hardly unknown in other countries, but it seemed especially prevalent in the places we visited in China, and not only in the big tourist spots. Many of the girls were done up in hanfu, which was quite nice to see; it would be a bit like 21 year old girls in Britain taking days out to Regents Park dressed in Georgian era dress. You’d also get the hanfu-attired girlfriends photographing their ordinarily-attired boyfriends, though I think I only saw one man dressed in hanfu himself. I think in general there were more young couples, and fewer large groups of young people, than on the streets of Britain.

Cars

One thing that gave me the alternative modernity vibe particularly strongly was walking next to busy highways in Guangzhou, where most of the cars were domestic, and almost all were electric. This made the sound of the roads oddly quiet, relatively speaking – the noise was from rolling tires, not engines, and when a petrol engine did go past it was a noticeable exception. There were a lot of BYDs, which I was familiar with as they’ve recently been introduced in Britain, but mostly it was brands I’d only read about, such as XPeng, Zeekr or Beijing auto, or never heard of at all, like GAC, Denza, AION or Chery. There were also quite a lot of Toyotas, BMWs, Mercedes and Teslas, but Chinese brands definitely predominated.

It was funny that the petrol engines you did hear always seemed to be from German cars, and you can see the dilemma of the German car manufacturers; they still sell a lot in China, but this is declining, and Chinese brands are increasingly encroaching in Europe and in their overseas markets. There were very few American cars except for Teslas, and very few Korean ones, which I found surprising initially, considering how dominant they have become in Britain in recent years, but apparently sales have been low since 2017 due to boycotts caused by Korea’s deployment of a US missile defence system (THAAD).

We’re still just at the beginning of the Chinese car export boom, and there will be a lot more Chinese cars on the world’s roads over the next ten years. If you look at the website for one of the aforementioned brands, they’re inevitably just about to launch in Britain, or already have.

Trains

Travelling around on the high speed rail network is an amazing and sometimes uncanny experience, where things feel, for the most part, very efficient and also very tightly controlled (we only went on the new high speed rail lines, the older rail lines are probably different). You can only enter the vast, airport style high speed rail stations by scanning your passport (or ID card for Chinese citizens), which also has to be linked to your ticket. In fact, for all intents and purposes, your ID document is your ticket: this is China’s ‘real name verification’ system which is also required in various other cases such as the mobile phone service (or bizarrely, to visit the museum of the Opium War in Humen).

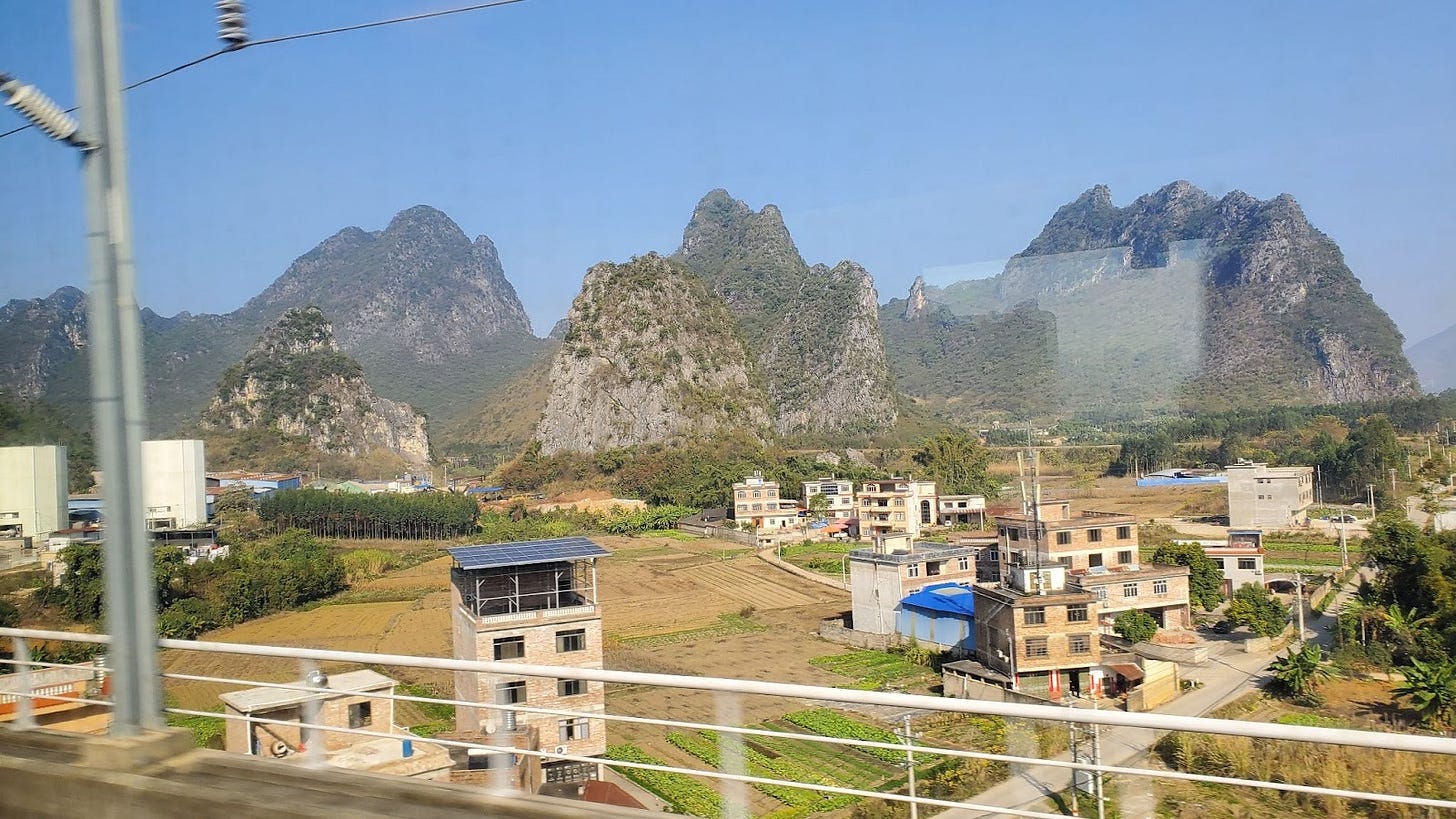

You do get a somewhat authoritarian vibe when you’re required to scan your passport for every single train journey, but the system works, and there were barely any delays. The journey between Guangzhou and Chongqing in particular was an amazing experience, travelling though hundreds of miles of mountain landscapes at nearly 300 km/hr. We didn’t visit any of rural China, but from the train you could see that many people were still engaged in small-scale agriculture. It was weird to travel from a city that felt far more advanced than British ones, to a countryside that seemed far less. China’s alternative modernity is not evenly distributed.

Reportedly the network has been massively overbuilt, with only a minority of lines being profitable, and we saw evidence of this in the cheap tickets, often empty carriages, and high speed rail stations in relatively sparsely populated locations. This may be a negative for the Chinese taxpayer, but it’s great for the traveller. The only real negative on the train network is the inescapable loudspeaker smartphone slop.

Summing up

I don’t think I can really ‘sum up’ without saying something trite. But I don’t think you’ll get an experience like this anywhere else, and I’d recommend it to anyone. This is a good article on tourism in China in general, about the practicalities, where to go etc. Despite, as he writes, the corpus of “I went to China and here are my field notes” articles being both large and tiresome, I hope readers have found this one interesting.

Great article. I had exactly the same thought as you on the train across rural China - so much agricultural work that looked backbreaking. I was also struck by just how many biomes China has that are relatively densely packed. I thought Macau was a total dump, like what I imagine North Korea to be plus some big casinos.

The thing that stood out to me about the police state was when a bus I was on going through the countryside in Yunnan was pulled over and everyone except us was brought out and briefly interrogated by the police. Unsure if there was genuinely a manhunt on (in which case fair enough) or if this was routine police harassment in this part of the country.

Great article. I am actually considering a visit to China with my dad at some point. He is a massive Sinophile. I think I would lean to going more western and more rural though. I loved the idea that the CCP are powerless against smart phone slop.