Getting to Denmark on immigration: how to speak softly and carry a big stick

Denmark's immigration policy: how much is it a model to follow?

By the end of their 14 years of rule over Britain, the Tories found themselves in the worst of all possible worlds on immigration, one that neither pleased their supporters nor mollified their enemies. They had presided over unprecedented and ever increasing numbers, while claiming for most of this period that they were going to bring them down. The supposed economic benefits were little in evidence, instead post-Brexit we got a boom in immigration of the dependants of low-paid care workers and students. And despite promising explicitly to do so, they couldn’t even manage to prevent people smugglers sending small boats across the channel.

As a result, by the eve of the election only 15% of potential voters thought they were the best party for handling asylum and immigration, well below the scores for Labour, Don’t Know, and None.

While even their own supporters had come to think them useless on the issue, much of the left-wing commentariat was convinced that the government was viciously hostile to immigration and was presiding over a Britain fast sliding into fascism. What accounts for this discrepancy?

The answer is that the Tories did the opposite of Theodore Roosevelt’s maxim to speak softly and carry a big stick. While some individual MPs and ministers took the issue seriously, taken as a whole the party spoke loudly but carried a small one. Their opponents heard them speak loudly, from Cameron’s pledges to cut immigration to the tens of thousands, Suella dreaming of flights to Rwanda, to Rishi promising to stop the boats. But their supporters started noticing more and more the gap between their empty rhetoric and the continually rising numbers.

Getting to Denmark

As Francis Fukuyama recounts in The Origins of Political Order (a fantastic book I wholeheartedly recommend), the challenge of creating good political and economic institutions has been described by social scientists as ‘getting to Denmark’. As he writes:

“For people in developed countries, “Denmark” is a mythical place that is known to have good political and economic institutions: it is stable, democratic, peaceful, prosperous, inclusive, and has extremely low levels of political corruption. Everyone would like to figure out how to transform Somalia, Haiti, Nigeria, Iraq, or Afghanistan into “Denmark,” and the international development community has long lists of presumed Denmark-like attributes that they are trying to help failed states achieve.”

As Fukuyama recognises throughout his works (e.g. see the National Identity chapter of Liberalism and its Discontents), a cohesive national identity shared by a large majority of citizens is a prerequisite for the ‘Danish bundle’ of nice things. While you can have some of the positive attributes like peace and prosperity without one (e.g. see Dubai), you cannot do without it if you also want to have a successful liberal democracy.

Liberal democracy requires that people behave politically as individuals within a single larger community and accept political defeat with good grace, not as members of tribal communities for whom inhabiting a parallel society or violent insurrection is preferable to ‘foreign rule’.

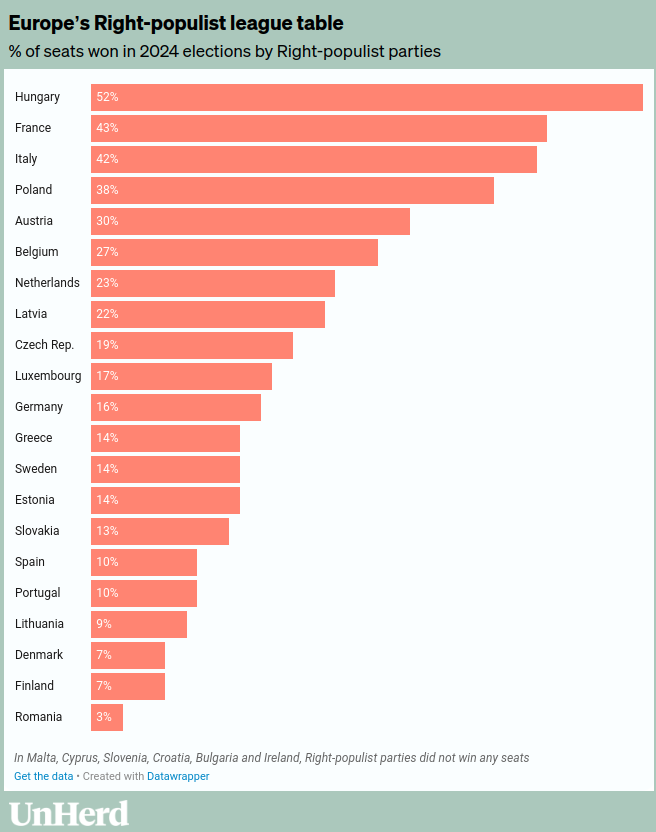

Mass, unselective immigration into liberal democracies poses a grave threat to their cohesive national identities and political stability. Most of the Western world has seen the rise of right-wing populism this century because Western governments have failed to control immigration to the satisfaction of their electorates, and given demographic and political trends there is no sign that the problem is going to go away.

As Ed West wrote about a couple of years ago, Denmark took a different path on immigration (asylum specifically) from most Western countries: the result was the neutering of right-wing populism in the country.

In the last few years Denmark has become a symbol of how to do immigration right from the restrictionist perspective. In this article I want to dig deeper into how the Danish immigration system works and to what extent it is indeed a model to follow.

What is the Danish model of immigration?

Labour migration

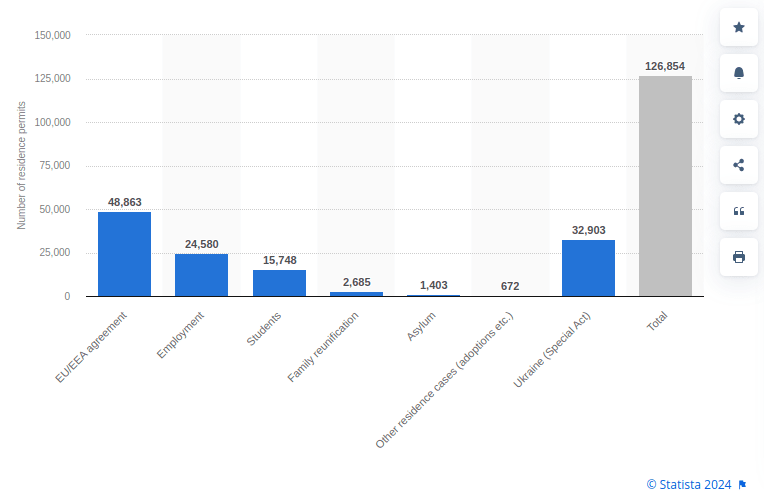

Most of the commentary on Denmark’s immigration system focuses on asylum. But as with most countries, labour migration is generally the biggest single source of immigrants, see the stats below for 2022 (Ukrainian refugees were the largest single source in this particular year, but obviously this is unusual).

As an EU member much of its migrant labour needs are satisfied from elsewhere in Europe. However it does also accept significant numbers from outside the EU and the numbers are rising: in 2022 21,533 of the work permits were for non-EU nationals. Scaled to the British population, this would be almost 250,000 permits, which is in fact pretty much the actual equivalent British total number of all work permits for that year. So in terms of the numbers of work permits issued, Denmark is not particularly restrictive, though it does have an unusually high salary threshold.

Denmark is more restrictive though on permit length and ease of gaining permanent residence. Work permits are issued for a maximum of four years at a time, and can only be extended for a job continuing in the same position as the original permit was issued for. Permanent residence can be applied for after living and working in Denmark for eight years. In Britain by comparison health and social care visas, for example, can be issued for a maximum of five years at a time, and indefinite leave to remain can also be applied for after five years.

In general then, Denmark is not super different from other countries on labour migration. The same forces are at play, businesses play up the labour shortage and lobby for more visas, and the numbers are relatively high as a proportion of the population, though acquiring permanent residence takes more time.

The debate is different through, and purely economic concerns are not the only ones discussed. In 2023 the employment minister Ane Halsboe-Jørgensen came out against relaxing immigration rules to enable companies to recruit more foreign labour, saying:

“As a government we must have an eye on everything. The question I have to ask myself as minister, which individual employers don’t ask themselves is, that if they get those workers, let’s say from an African country, what does that mean for the cohesive force [of society]”.

As we will see later, this different approach can be seen in who is given citizenship, even if the raw numbers of labour migrants are quite high.

Health and social care

As a segment of labour migration, health and social care is interesting from a British perspective because it makes up such a large proportion of recent labour migration here, 350,000 visas (including dependants) in 2023, making up 75% of skilled worker visas to Britain. Britain also has longstanding recruitment of foreign doctors and nurses: in 2019 30% of doctors and 15% of nurses were trained abroad.

Denmark is not immune from this international trend, though it does recruit from abroad at a far lower rate: 9% of its doctors and 2% of its nurses were trained abroad. Regarding care workers, a recent article describes a new deal to recruit 1000 social care staff from abroad (from a base, it is implied, of zero). Readers from Britain, where 78,000 care worker visas were issued between June 2022 and June 2023, may view the fact that 1,000 visas in Denmark is worthy of a news story much like Dr Evil’s one million dollar ransom demand (even scaled by population it is much less), but clearly the same forces are at play to some extent.

Again though we can see in this article an example of the different Danish approach. Minister for Immigration and Integration Kaare Dybvad Bek said:

“It is important that we separate immigration policy from foreign labour. We give tens of thousands of residence permits to workers every year and I don't consider these things to belong together”.

Compared to other Western countries then, again Denmark goes further in separating temporary foreign labour from permanent immigration, i.e. taking an approach that is normal among immigrant receiving countries outside the Western world, like South Korea.

Asylum

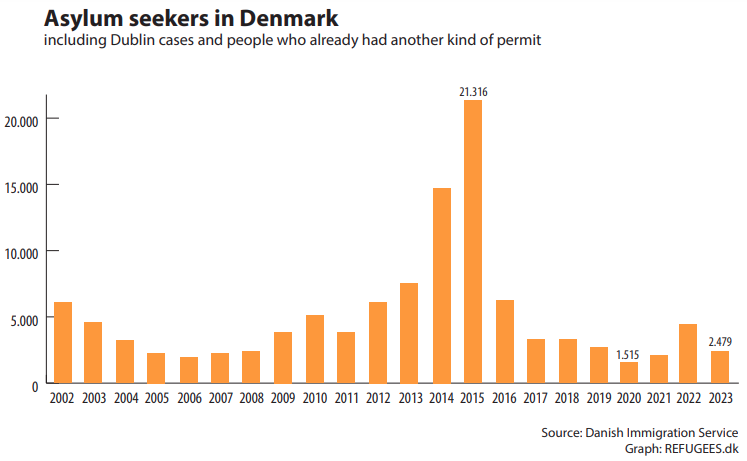

It’s Denmark’s asylum policies that have made it most famous in the realm of immigration policy. After the refugee surge of the mid 2010s, peaking in 2015 when Denmark received over 20,000 asylum seekers, the country introduced legislation enabling asylum seekers’ residence permits to be withdrawn once their home region had been declared safe.

In most Western countries asylum is in practice just another route to permanent settlement. Denmark is unusual in its emphasis on asylum being for temporary protection and on refugees returning to their country of origin once it is safe to do so. One of the issues with asylum in say, Britain, is that those whose applications are rejected rarely actually leave the country. Rejected asylum seekers in Denmark stay indefinitely in a ‘return centre’ until they choose to leave Denmark.

2019 was the year of the Danish ‘paradigm shift’ where the focus of policy shifted from integration to return to countries of origin. That year Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen stated that her government’s goal was ‘zero asylum seekers’ (referring to people arriving via irregular channels: Denmark still accepts an annual quota of 200 of the most vulnerable asylum seekers from the UNHCR). Since 2015 numbers have dropped to less than 5,000 per year, with around a quarter of these being ‘remote registrations’ who already had a residence permit to stay in Denmark.

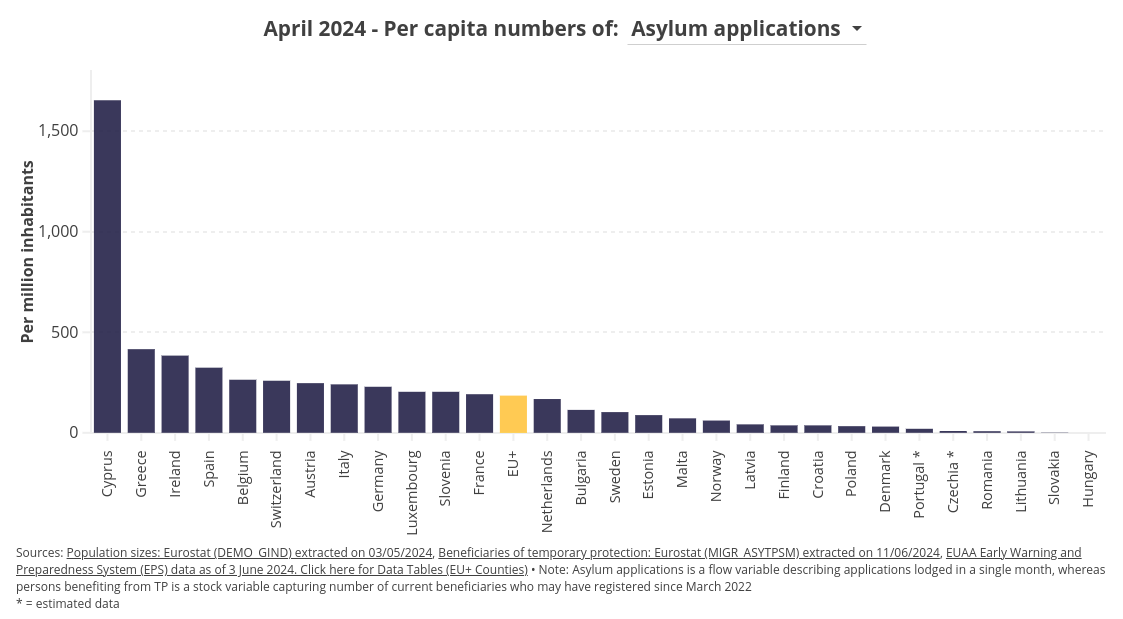

This is clearly not the zero asylum seekers of Frederiksen’s claim, and in fact as a proportion of Denmark’s population of 5.9 million was not that different from Britain, where asylum claims were about 40,000 a year from 2015 until 2020 (though much more in recent years). It is low for Europe though: as of April 2024 Denmark had one of the smallest per capita rates in the EU, and the smallest in Western Europe (I am cleaving to Portugal’s spiritual identity here as belonging to Eastern Europe).

Denmark then has not definitively solved its asylum issue nor achieved ‘zero asylum seekers’. But its model is far more effective than those of its peer countries: it has relatively few claims compared to them and has taken effective steps to prevent the asylum route merely being another path to permanent settlement.

Sweden is the obvious comparator here of what can go wrong. Its troubles with gang crime are well known and have now become so extreme that they are now even being exported back to refugees countries of origin. Iraq recently sentenced two Swedish-Iraqis to death for a gang killing: Sweden, of course, protested on human rights grounds (I’d love to have witnessed the reaction of Iraqi government officials to this).

Speaking of human rights, it’s notable that Denmark has enacted its policies while remaining a member of the ECHR. I’ll write more in the conclusion about what this says about the claims by those on the right of British politics that leaving the ECHR is a prerequisite to enacting their preferred asylum policies.

Crime

Denmark is certainly tough when it comes to foreign criminality, as of 2022 the government aimed that foreigners who had been given a prison sentence would always be deported, some of whom will serve their sentences abroad, e.g. in Kosovo.

This is one issue where we do see Denmark coming into conflict with the ECHR, with cases against the country making up a larger proportion of caselaw on expulsion since 2018 than any other member country. The overall effect though does not seem to be to change the Danish model too drastically, of the 11 cases against Denmark since 2018, only 3 resulted in a violation being found.

Family reunification

As with asylum, Denmark has a reputation as being tough on family reunification migration: its ‘24-year rule’ requirements regarding the age of the couple and their economic status have been invoked as evidence that it ‘beat mass immigration.’

The numbers appear small and they do show a downward trend in recent years (see here, page 11), from 7,790 in 2017, 4,529 in 2020, to 2,762 in 2023. However Denmark is a small country and the numbers are broadly in line with the British ones as a proportion of the population, where family unification visas were issued at a rate of about 38,000 per year from 2009 until 2022.

Like many of Denmark’s immigration policies, it is not that these policies are really hugely restrictive or amount to ‘beating mass immigration’. It is only that they are less extreme than somewhere like Sweden, which over the last few years has issued around 20-30,000 family reunification permits per year, over three times that of Denmark as a proportion of its population and approaching the absolute British numbers. Or Germany, which issued over 121,000 such visas in 2023, around three times that of Denmark by population.

Citizenship

Citizenship can be applied for after living and working in Denmark for nine years. This is on the high end for Europe: Britain requires 5/6 years, and Germany used to require eight years but recently changed it to five. But it’s by no means an extreme outlier: Switzerland and Italy for example both require ten years.

Citizenship (and permanent residence) applications are rejected for those who have been convicted of serious crimes, and delayed for a certain number of years for those who have committed less serious ones. Again though this isn’t unusual: Britain and Germany for example have similar restrictions.

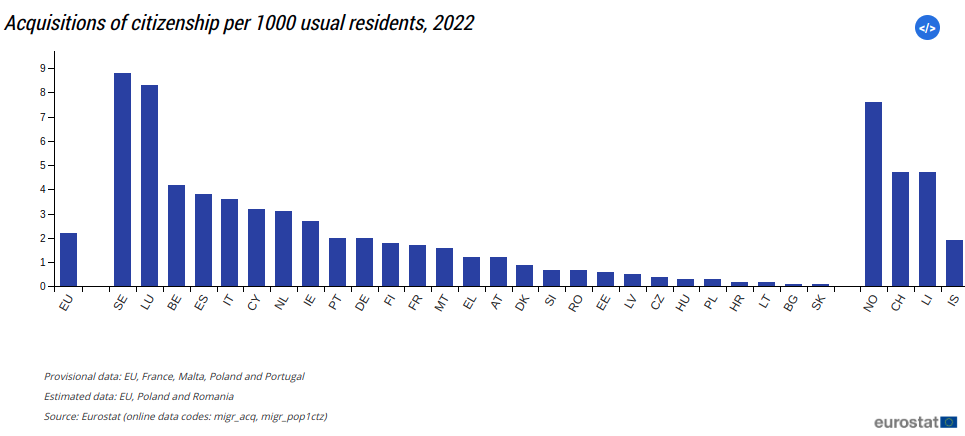

So in theory Denmark is on the restrictive end, but not unusually so. How do things play out in practice? Actual numbers of grants of citizenship are low, only 1,781 being granted in 2019, the lowest for 40 years. This is around eight times less by population compared to Britain’s roughly 160,000 that year. Compared to other EU countries, in 2022 Denmark’s number’s of citizenship grants as a proportion of its population was the lowest in Western Europe: France and Germany granted twice as many, the Netherlands three times as many, and our favourite example of Scandi-madness Sweden: 10 times as many.

On average it takes 19 years to acquire Danish citizenship, and it may be the combination of various requirements, none of which are particularly onerous on their own, that account for this.

Disaggregation of immigration by source region

The fact that Denmark categorises immigrants by region of origin is perhaps where it departs from the liberal Western norm most significantly. As the European Commission disapprovingly notes, the Danish state distinguishes between Western and non-Western migrants in its official statistics, as well as having a special category of MENAPT (Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan and Turkey) for categorising migrants from Muslim countries who are overrepresented in crime and unemployment statistics and who pose particular problems for integration into Danish society.

As an aside, you might have thought that the European Commission would be grateful to Denmark for its policies that dampen the appeal of eurosceptic parties like the Danish People’s Party. This party was the original right-wing populist party in Denmark which kickstarted its official immigration-scepticism in the late 90s. Contrary to the situation in much of Europe though, its support has been declining since its high in 2015 when it became the second largest party. The adoption of its policies by the political mainstream has removed much of its raison d'être.

Back to the categorisations: as the Minister for Immigration and Integration at the time, Mattias Tesfaye, explained in 2020:

“We need more honest numbers and I think it will benefit and qualify the integration debate if we get these figures out in the open, because fundamentally, they show that we in Denmark don’t really have problems with people from Latin America and the Far East. We have problems with people from the Middle East and North Africa.”

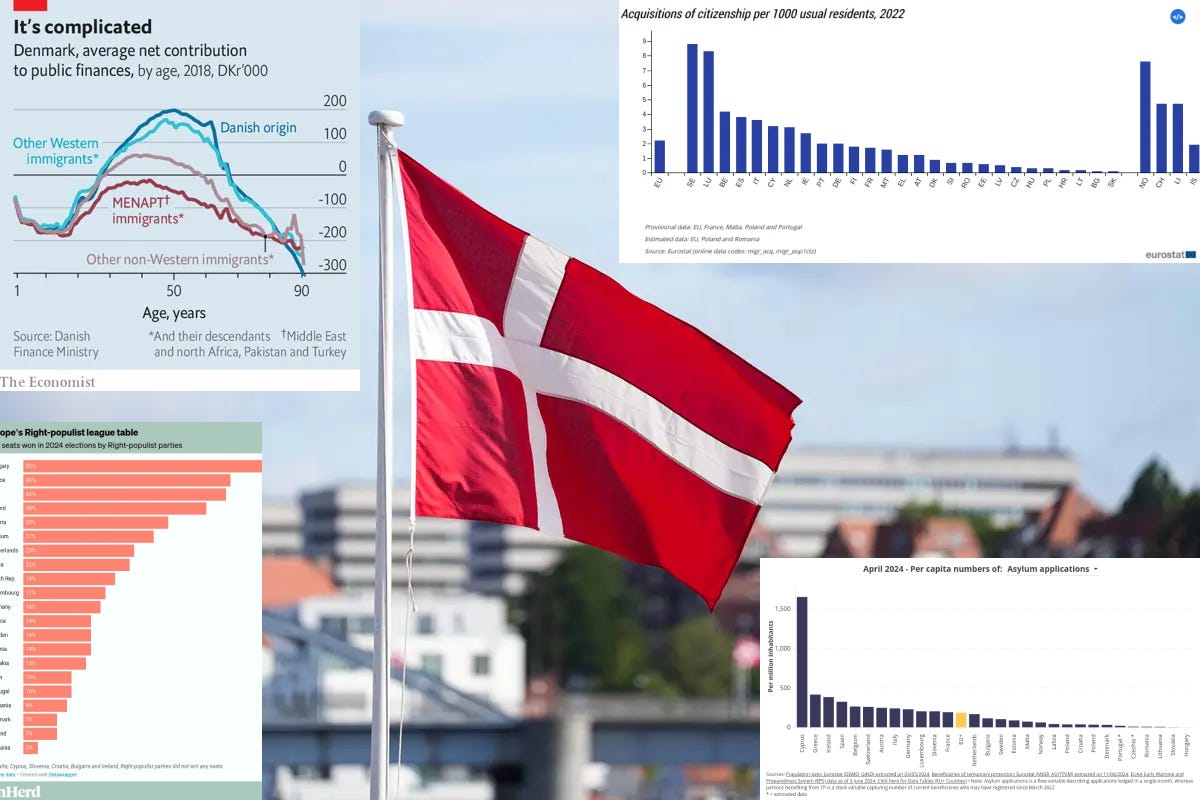

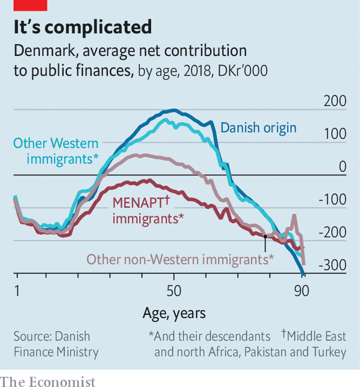

These categorisations are what enabled the production of the Economist’s famous graph showing that non-Western immigrants on average made a negative contribution to the country’s finances (equivalent to 1.4% of GDP) and that MENAPT migrants were even worse.

Most other Western countries fail to disaggregate immigration in this way, meaning immigration restrictionism crudely targets raw numbers, such as Reform UK’s ‘Net Zero immigration’. A smarter policy would be to identify which sources of immigration are actually problematic and to cut them off, while being quite liberal on sources that are beneficial. But overly strict adherence to liberal egalitarian principles makes this impossible even if in practical terms it would vastly improve outcomes and dampen support for right-wing populism.

Apart from informing the ‘parallel society laws’ (see below) these different categorisations do not seem to have particularly wide application in Denmark. However the fact that they are made explicit at all is a sign that the country is willing to accept the idea that immigration overall is neither inherently good or bad but depends on the characteristics of the migrants themselves and how they interact with the host nation.

Integration policies

It’s clear that a big driver behind Denmark’s unusual immigration policies is that it takes the unity and integration of the population seriously, especially compared to anglosphere countries. Integration policies are not the focus of this article but I’ll briefly describe some where you can see the same intentions.

On housing, Denmark actually implements the wildest fantasies of the participants in the British social housing debate with its parallel society laws. Places which perform poorly on indicators of crime, income, employment and education, and which have over 50% of residents from a non-Western background are targeted for redevelopment. Their share of social housing is reduced to 40% and private housing is built instead.

Denmark has also made it illegal to fly foreign flags, and of course has banned the burqa (though the latter policy is not unusual for Europe).

Overall demographics

So what does this all mean for Denmark’s overall demographics? The country is diversifying just as other Western countries are, although more slowly. The proportion of Danes of Danish descent has been decreasing by 3-4% per decade since the 90s (96% in 1991, 93% in 2001, 90% in 2011, 86% in 2021), although other Europeans make up around half of those of non-Danish descent.

If we compare with Britain, the white British population percentage has been decreasing at almost twice the rate, at 6-7% per decade this century (c. 94% in 1991, 90% in 2001, 83% in 2011, 77% in 2021/22), with other Europeans making up only around a quarter of the minority population.

If we were to take these stats at face value and project current trends into the future, it would take over 100 years for Danes to become a minority in Denmark, while in Britain it would happen in 40-50 years. And if we looked instead at when all people of European descent were projected to become a minority in both countries, it would take 70-80 years for Britain vs around 250 years for Denmark.

In reality things are far more complex than statistics like these portray due to assimilation, intermarriage, changes in how people identify, and future changes in levels of immigration. For example, almost all Europeans tend to assimilate to the majority population over a couple of generations, and some proportion of non-Europeans will too. And while current global trends indicate the same or an increased rate of immigration over the next few decades, current trends can of course change in unpredictable ways.

So projections like these are unlikely to be accurate guides to what actually happens many decades or centuries from now. I think they’re worth laying out anyway to show the overall situation.

Lessons from Denmark

So what are the overall lessons here? Denmark is still a liberal democratic Western country experiencing the same pressures as the rest, and it is diversifying. The process is going less quickly than in some other countries but it is still the same trend. Anyone demanding an immigration moratorium and a reversal of increasing diversity is not going to be satisfied with the Danish policy.

Denmark is more successful than peer countries though in three ways. Firstly by slowing down the process and making it more manageable. Secondly by facing up to the fact that not all immigration is the same and trying to prevent its more damaging manifestations. And thirdly by achieving national political consensus and relative policy effectiveness on the issue.

Rather than Denmark being extreme, the situation is really that it is a moderate country surrounded by extremist ones like Sweden and Germany. So what lessons could other countries take from Denmark?

Go further in separating labour migration from citizenship

Go further in separating labour migration from citizenship by tightening citizenship requirements and establishing a political norm separating the two. Denmark is no Dubai but it is going further than other Western European countries in this direction.

As Immigration Minister Kaare Dybvad Bek said above, it is necessary to separate immigration from foreign labour. Temporary labour migration is going to happen anyway, even in countries like Israel and South Korea, the difference is how they handle it. There is no reason why temporary labour migration must inevitably lead to demographic transformation of a country’s citizenry.

Set a goal of zero asylum seekers arriving via irregular channels

It’s obvious to any fair-minded observer that the asylum system has long been captured by people smuggling gangs and now means a large and never-ending stream of young male claimants. Western countries should recognise that a system set up to help those fleeing war and political persecution in mid 20th century Europe no longer works in the 21st century world.

The goal should be to end the current farcical situation, and instead accept a small number of the most vulnerable people on a temporary basis, as Denmark is attempting to do with the UNHCR quota. This can of course, all be done while being a member of the ECHR.

The problems achieving this are national not international: zero asylum seekers via irregular channels was the intention, for example, of Britain’s Illegal Migration Act 2023. But as we know, the way it was crafted and its implementation left much to be desired and it achieved nothing. The reasons for this are not super clear to me, but Rishi Sunak’s unwillingness to confront more liberal elements of his party like the Tory Reform Group stand out to me as the primary reason.

Disaggregate immigration by source region

Disaggregate immigration by source region in national statistics, and craft policy with this in mind, rather than simply treating ‘immigration’ as one block. Restrictive policy is needed for regions where immigration disproportionately results in crime, terrorism and parallel societies. For other regions, where immigrants assimilate easily, there’s no real need for restrictive policies at all.

Denmark is only using these categorisations in a limited way at the moment, but the fact that they exist give it the opportunity to do more in future. Simply having the data in the first place, as Neil O’Brien has written, is the first step.

As much as is possible, speak softly and carry a big stick

Fundamentally immigration policy requires boring but effective administration, carried out over a long period. It’s not something that can be solved with short, flashy interventions, which, as with Britain’s Rwanda plan, often achieve nothing but riling up political opponents.

This is not to discount the role of firebrands at all, after all it was the populist Danish People’s party that first brought the issue onto the agenda, and the somewhat Suella Braverman-like Inger Støjberg, immigration minister between 2015-2019, was not afraid to take controversial actions.

But as Denmark showed, at the end of the day actual results require more than this, through the dull, everyday business of government, and as much as is possible, this should be the approach.

The opportunity for the EU

I’ve always been amazed that the EU itself does not take the lead on tackling illegal immigration for its member states. It’s so ideologically captured by end of history universalism that it’s missing the opportunity to massively increase its popularity. The EU needs to step up and become the actual defender of European civilisation, not merely an unmoored institution that happens to be located in Europe.

The EU should see Denmark as its model. Instead of German NGOs frustrating Italian attempts to control illegal immigration, there should be a fleet of EU funded Thyssenkrupp patrol boats in the Mediterranean, guided by the EU’s Galileo GPS system, deterring migrant smuggling boats and arresting members of organisations trying to frustrate the policy.

The EU is a way for Germany to transmute its own identity into a European one. There is, clearly, strong reluctance in Germany for the assertion of any sort of identity based social policy such as restriction of immigration, Ausländer Raus notwithstanding. But if it were für Europa?

I'm certainly more of a nationalist when it comes to immigration to Europe, especially both Muslim and African immigration. But for the US, I'm willing to accept a lot of low average IQ Latin American immigration on humanitarian grounds if we will also continue aggressively recruiting global cognitive elites.

The frog is in a slow cooker.