An alternative history of British immigration policy: 1964 - 2024

Douglas-Home killed in 1964, Butler as PM. Powell becomes home secretary and later PM. No Ted Heath, no EU. John Smith not Tony Blair as Labour leader.

Enthusiasts for whatever our current system of immigration is often justify their preferences on the grounds of inevitability, even for changes that were only enacted in the very recent past in response to specific circumstances. ‘Inevitable social trends’ are often the result of small initial actions followed by path dependency and the human tendency to conform to established norms.

With this in mind, I want to imagine a plausible alternative immigration history for postwar Britain where a more restrictionist and more importantly more selective path was taken that recognised and headed off the potential for some streams of immigration to create large alien communities and a divided society.

So, here goes, in the form of a newspaper article from an alternative 2024. My point of departure is a different result to the Alec Douglas-Home kidnapping plot of 1964; footnotes are there to explain what happened in the real history.

In a Europe increasingly disillusioned with mass migration, the ‘British model’ gains appeal

The June 2024 European elections demonstrated incontrovertibly that the political backlash in Europe over migration is not going away: in fact it is growing stronger. Far right parties have made huge gains, the Belgian premier has resigned and French President Emmanuel Macron has called new elections, and even in Germany, a country where the taboo on nativism is the strongest, the AfD is rising.

Europe has had a fraught relationship with migration for decades, often initially welcoming it, like the German Gastarbeiter programme of the 1960s or Sweden’s historically open refugee programme, only to later, but never very successfully, attempt to crack down. Increasingly though, voters see the issue as out of control, hence the rise of parties like the RN in France, the PVV in the Netherlands, the AfD in Germany, or the Sweden Democrats.

Britain though, stands out. Compared to the rest of Europe, Britain has controlled immigration remarkably effectively ever since the 1960s: as a result immigration is rarely an issue in British politics and the populist waves of 2016 and 2024 never rose there. Britain was long viewed as a somewhat backwards curiosity for its policies in the rest of Europe. But now politicians across the continent are increasingly pointing to Britain as an example of a country which, they say, got it right.

The first evidence of this was in Denmark, which historically shared much with Britain, including its scepticism towards the EU, but which had been, until the 2010s, more open to immigration and refugees. Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen, in her 2019 campaigning promising to tighten Denmark’s asylum laws, repeatedly referred to the ‘Den Britisk Model’ of immigration.1 In the last few years though, the British model has gained more advocates, including in countries like Germany which historically resisted it.

What is the British model of immigration?

Britain has long been different from the European norm on migration. While the country has certainly experienced immigration and has become much more diverse than it was in the 1950s, there is nothing like we see in France, Germany or Sweden in terms of ethnically divided cities or social and political unrest.

While more liberal-minded Brits sometimes bemoan their country’s path, others point to the negative effects in Europe that they have avoided. The British look with horror at the terrorist attacks suffered across the channel in France, pointing out that Britain has not suffered a single terrorist attack since the IRA ceasefire in 1997. Horror also greeted phenomena like the 2015 Cologne sex assaults, events that would be unheard of in Britain. More recently, the Israel-Gaza war failed to become much of a political issue in the country and Jewish Londoners describe Britain as the “last safe place in Europe”.

London’s tech and finance industries remain a destination for skilled migrants from all over the world, from Europe especially, while British universities attract hundreds of thousands of international students. But there is no refugee problem, no ethnic ghettos. Britain, some say, gets the immigration it wants. Europe has to deal with the immigration that it doesn’t.

How did Britain become different?

In the decade and a half following the second world war it looked like Britain was heading down a similar immigration path that would eventually be followed by other European countries like France and Germany. This pattern was an initial influx that was expected to be small and temporary, followed by permanent settlement and an unintended but ever-growing immigrant population.

As part of the attempt to hold on to the British Empire, the British Nationality Act of 1948 had created a single citizenship category of ‘Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies’ permitting completely free movement throughout the empire and commonwealth. This freedom was almost immediately taken up in ways not predicted or welcomed by the British government. A notable early example was the arrival of hundreds of West Indian immigrants that same year on board the ship the Empire Windrush. Though little remembered today, this event caused much comment and controversy in Britain at the time: the Labour government of the day opposed the arrival but as they could not do anything legally to prevent it, they merely aimed to discourage such arrivals in future.

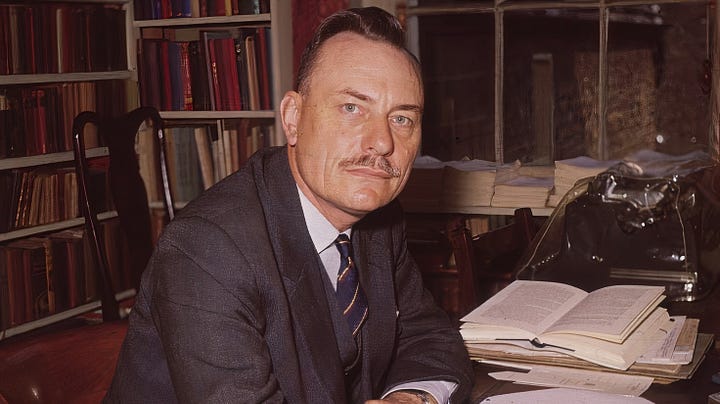

Empire and commonwealth migration did however continue into the 1950s. Overall numbers were relatively small, with the 1961 census recording a non-white population of only 1%. In 1962 however, in response to rising numbers of immigrants and growing discontent among the population, the Conservative government passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act ending the unrestricted rights of Commonwealth citizens to migrate to Britain. Some Conservative leaders however, most notably future home secretary and prime minister Enoch Powell, thought that the restrictions did not go far enough.

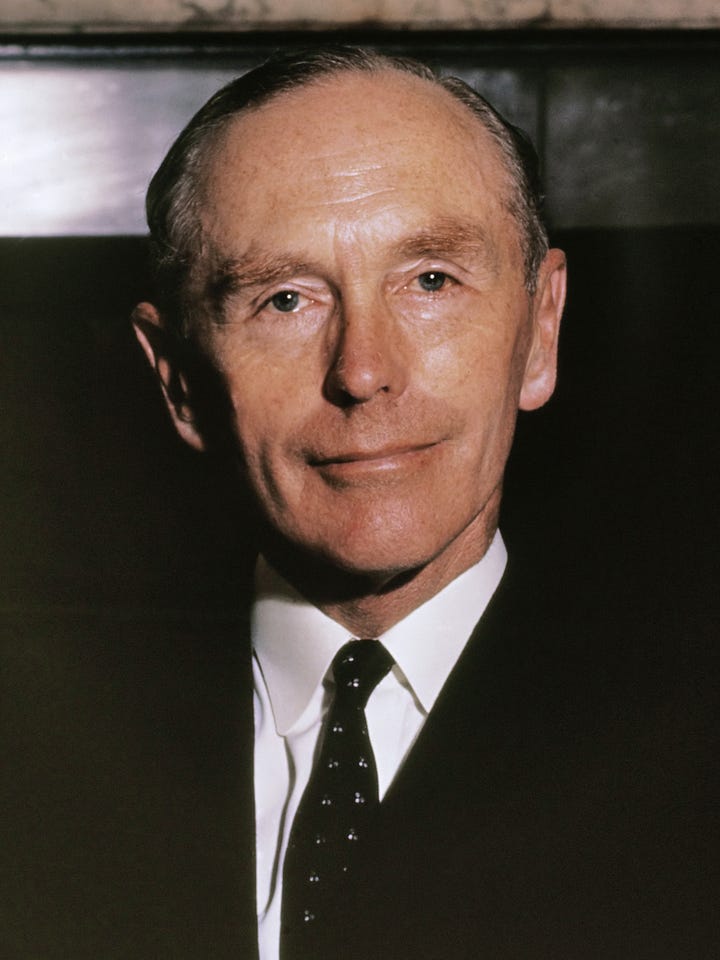

Without Powell the British model may never have come to fruition and it was only due to the improbable death of Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home in the Aberdeen kidnapping plot of 19642 that he became home secretary at all. In 1963 Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had resigned and been replaced by the aristocratic Douglas-Home, in a secretive process orchestrated by what had been called by party chairman Iain Macleod an ‘old Etonian magic circle’ within the party.3 Powell, who was minister of health and a supporter of Macmillan’s deputy Richard Austen (‘Rab’) Butler, whom many had expected to become leader, refused to serve under Douglas-Home in protest at the way he had been installed by the party.

What followed was a mix of the tragic and the absurd. In April 1964 Douglas-Home was driving alone to the house of his hosts near Aberdeen, having just spoken at a Scottish unionist conference, when a group of left-wing students from the nearby university initiated a kidnap plot that seemed more performance art than serious attempt, at least initially. The students intercepted and blocked his car, forced him out and into their own, and drove off with him, headed for Aberdeen. In the subsequent inquest it was established that the students had only intended to hold the prime minister for a few hours and then release him, but in the thick fog their car veered off the road and crashed: Douglas-Home as well as one of the students was killed.4

The Conservatives now had to hurriedly hold their first ever leadership election. With not much time before the general election, Rab Butler was persuaded by Powell and others to stand, stood unopposed and became prime minister. The Conservatives were not much loved by the electorate by this point, but due to the combination of public anger with the left over Douglas-Home’s death and the relative popularity of Butler, they managed to narrowly win the 1964 election. In a move with far-reaching consequences, Butler then appointed Powell as his home secretary.5

Over the next several years, Powell transformed the immigration system in several important and long-lasting ways. Under his leadership the home office introduced the ‘primary purpose’ rule which made it almost impossible for existing migrants to bring over foreign spouses if they were from a country that had been identified as a significant source of marriage migration.6 This mostly affected nationalities practising arranged marriage, mostly men working in Britain from the Indian subcontinent, and prevented a common migration route that other European countries experienced.7 Powell also massively bolstered the ability of the historically under-resourced Immigration Branch, as it was known then, to enforce immigration law at the border.

Powell’s policies were not without controversy and started causing increasing friction between him and Butler, and especially with Chancellor Iain Macleod who threatened to resign on several occasions.8 Yet Powell was an effective publicist, and his policies were highly popular with the electorate: this popularity was such that by 1967, according to surveys, Powell had become the most popular politician in the country.9 With Labour gaining in the polls, Butler and Macleod felt they had no choice but to go along with his policies to have a chance at the next election.

In spring 1968, Butler, having achieved his ambition of becoming prime minister but not wanting to fight the next election, announced his resignation.10 He hoped to make way for a younger moderniser like Ted Heath, and a leadership election was called. When he became home secretary Powell had not had a particularly large support base in the party11, but due to his popular policies it had grown throughout his tenure, and he entered the leadership race. Heath was still the favourite, with Powell predicted to come second, until opinion polling revealed that Powell was the only leader who would beat Harold Wilson’s Labour in an election. Despite many Conservative MPs having private misgivings about Powell, he narrowly beat Heath in the leadership election and then led the Conservatives to another narrow election victory over Labour later that year.

As Prime Minister Powell led the transformation of the relation between immigration and citizenship. As minister of health earlier in the decade he had welcomed medical staff from the Commonwealth to come and work in the NHS, but had wanted the migration to be temporary. The Immigration and Nationality Act 1970 altered the longstanding situation that British citizenship could be obtained after five years residence in the country. Immigrants could now come on two classes of visa. One class retained the right to apply for citizenship after five years residence, while the other class of visa specified that it was a work permit only and would not lead to citizenship. These latter class of visas were offered for five years at a time, with a maximum of two such visas allowed to any one person. Source countries were divided into those that had a cultural affinity with Britain and those that did not, with the former visas generally allotted to citizens of the former, and the latter type to citizens of the latter (with exceptions for certain classes of skilled workers).

Despite the popularity of the Powell government’s immigration and nationality policies, it started to bleed support in other areas. Later in his term, Powell, an economic liberal, made controversial reforms to the planning system, reducing the power of local councils to stop development of new housing and commercial real estate. Though today these reforms are widely seen as prescient and responsible for Britain’s relatively low property prices, at the time they were widely unpopular. These together with Powell’s attempted reforms to the NHS and to the, as he saw it, overweening power of the trade unions led to Labour taking a large lead at the polls. Thus in the 1972 election Powell lost to Harold Wilson, though significantly, Labour had promised in its manifesto no deviation from Powellism on matters of immigration and nationality.

Powell never returned to high office but his legacy has endured to this day. One aspect of this was his immigration and nationality system which persists largely unchanged, another was keeping Britain out of the European Community (as it was known then), against the wishes of europhile Tories like Ted Heath who had come so close to the premiership. The Labour governments of the 70s which followed Powell were equally anti EC, though for different reasons. By the time the Tories returned to power under Margaret Thatcher in the late 70s, the desire within the party to join had lessened, and instead, reducing the power of the unions and rolling back the state was seen as the solution to Britain’s problems.

Ironically, considering Powell opposed joining the European Community so strongly, the effect of his policies was to cut Britain loose from imperial or commonwealth ties and re-Europeanise British identity. His policies had caused controversy not only Britain but in the commonwealth as well. Powell regarded it as a meaningless institution: another piece of legislation under his government had been to end the ability of non-British commonwealth citizens residing in Britain to vote in elections. In response several countries including India and Pakistan left the commonwealth, and thereafter the institution sank into irrelevance.

Powell’s legacy continued mostly unchanged through the Conservative governments of the 1980s, but came under threat in the 1990s when Labour returned to power. Members of the ‘New Labour’ movement within the party, especially Tony Blair and Barbara Roche, advocated a Britain that was more open to the world, but Prime Minister John Smith,12 fundamentally a European social democrat, was sceptical of the effects this change this would have on workers rights and social cohesion and maintained the existing system, against much criticism from within his party.

In more recent years, Britain has somewhat opened up, especially since 2004 when bilateral agreements were made with several of the new A8 Eastern European countries to allow a certain number of workers into the country each year.13 The Powellite system of distinguishing between source countries has also enabled relatively liberal immigration policies with countries in much of Europe and the Anglosphere, while workers come mostly on temporary work permits from the rest of the world. Other routes though, which have caused so much controversy elsewhere, remain strictly controlled. Britain maintains an Australian-style policy towards migrants illegally crossing the channel, and the powerful Immigration Office, another of Powell’s institutional legacies, accepts only a very small number of refugees, despite Britain’s membership (some critics say theoretical membership) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

As of 2024, as the far right rises in Europe, British politicians are enjoying their newfound status as trendsetters and voices of reason and moderation across the continent. In fact this week several UK ministers are speaking at a conference in Brussels titled: The British model of immigration: what lessons can Europe learn? The prime minister opened the conference with these words: “For a long time Europe regarded us as pariahs on this issue. I welcome their change of heart, though I regret that it has taken this long.”

The real world

I chose the Douglas-Home kidnapping plot of 1964 as my point of departure because the ending of Powell’s political career by the Tory leadership despite his popularity among voters marked the clearest example in 20th century British history of the establishment overriding the wishes of the people on the issue of immigration. And because kidnap plots are fun.

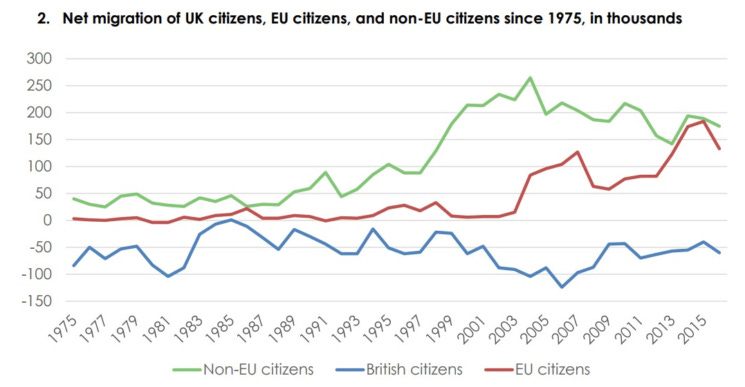

But in reality, despite Powell’s defenestration and subsequent anointed role as the bogeyman of British race relations, British immigration policy actually did remain pretty restrictionist until 1997. Harold Wilson’s Labour government passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 which restricted the ability of Commonwealth citizens to migrate freely to Britain unless they had a parent or grandparent who had been born there (against the opposition in fact of some Tories like Iain Macleod and Michael Heseltine), and the Immigration Act 1971 under Ted Heath’s Conservatives limited things even further. The Thatcher government maintained strict controls and tightened them in some areas. The British Nationality Act 1981 mostly abolished jus soli and in 1983 the ‘primary purpose’ rule was introduced to restrict marriage immigration, a route heavily used by immigrants from the Indian subcontinent.

Thus by the mid 1990s, the numbers coming to Britain still pretty much matched the numbers leaving, and while Britain was far more diverse than it had been 50 years earlier, the country was still 90% White British in the 2001 census. It has thus been said that while Powell the man was rejected by the political establishment, Powellism was quietly accepted until the time of New Labour. To some extent you can see Powell’s sacking as an example of a political tactic used when faced with rebellion, you crush the rebel leadership in order to affirm your authority and make an example of what happens to rebels, but you then quietly do much of what the rebels wanted anyway in order to head off further ones.

Thus in 1999 political scientist Christian Joppke could still write in his book Immigration and the Nation State that “Britain stands out as the Western world's foremost ‘would-be zero immigration country’, displaying an exceptionally strong and unrelenting hand in bringing immigration down to the ‘inescapable minimum’. The previous year Joppke described how “Britain has managed to contain unwanted immigration more effectively than any other country in the Western world”.

The main effect of my alternative history of an explicitly Powellite immigration policy then would have been an earlier and tougher restriction on marriage immigration and the establishment of truly temporary work visas. This would have made a significant difference, especially to arrest the growth of, especially, insular Mirpuri communities in the north of England. And it would also have established a stricter model less open to exploitation in subsequent decades.

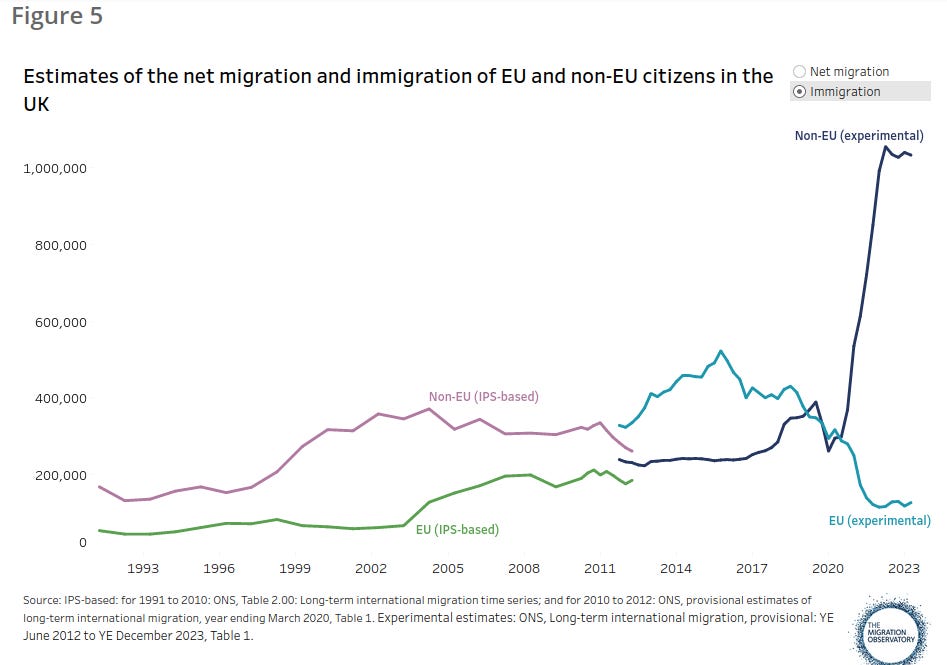

The real hinge points in terms of numbers and composition though were the New Labour and Conservative administrations from the late 90s onwards. New Labour’s actions to increase immigration such as, among many others, the abolition of the primary purpose rule, were significant, but perhaps even more so were the Conservative governments which followed them, which allowed immigration to increase to unprecedented levels. A point of departure in 1997 (no New Labour) or 2010 (a more conservative Conservative party) would have been significant. So even would have been one in 2019, when the obfuscation about ‘global Britain’ of the Brexit campaign allowed this faction of the Conservatives to take the anti immigrant sentiment of the Brexit campaign literally but not seriously, and claim they had taken control while massively increasing numbers from Asia and Africa.

Overall though, I wanted this article to emphasise how small initial changes can result in big differences in terms of results, and how ‘inevitability’ is a lazy and severely insufficient explanation for historical events.

Other articles you may like…

In reality of course, it is Denmark, not Britain, which pioneered a more sensible immigration model.

This kidnap plot was real (though unknown to the public until 2008) but in reality ended very differently with no harm done to Douglas-Home.

This was the last time a Conservative party leader was chosen in this informal way. The furore it caused led to the party establishing a formal process for the first time, first used in 1965 when Ted Heath won the leadership election.

In reality the kidnap plot ended with the attempted kidnappers abandoning the idea of intercepting Douglas-Home’s car and instead confronting him alone at the house where he was staying. The prime minister however managed to talk them out of kidnapping him after asking for some time to pack and offering them some beer. During the process he told them that if they did kidnap him “the Conservatives will win the election by 200 or 300”.

In reality, the unpopular Douglas-Home, viewed as aristocratic and out of touch, lost the 1964 election to Harold Wilson’s Labour. The result was close and it was claimed by many at the time that a different leader such as Rab Butler would have won. Ted Heath won the next Tory leadership election, appointed Powell as shadow defence secretary but then fired him in 1968 after his speech in Birmingham on race relations and immigration, christened the ‘rivers of blood’ speech by his enemies.

In reality, the ‘primary purpose’ rule was only brought in under a Thatcher government in 1983. It was effective but did not manage to completely stop marriage migration, and was repealed as one of the Blair government’s first actions in 1997.

In reality, one of the results of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and subsequent acts was to transform temporary labour migration into permanent and ongoing settlement via marriage migration. Before the early 1960s the vast majority of South Asian migrants in Britain were male, intending to work temporarily and return home. The fact that the immigration restrictions of the 1960s heavily limited primary immigration but permitted marriage migration set the pattern of settlement of these groups for decades to come. See part 5 of British Immigration Policy Since 1939 (Spencer 1997) for more on this.

In the real world Macleod, a liberal, who had been a close friend of Powell for years, voted against Labour’s 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and fell out with Powell permanently over the ‘rivers of blood’ speech.

A distinction that he only attained in the real world after his 1968 speech once he was out of power.

In reality Rab Butler retired from politics in 1965.

In the real 1965 Tory leadership election Powell only got 5% of the vote.

Who in reality died of a heart attack in 1994, allowing Tony Blair to become leader.

In reality the Blair government vastly underestimated the numbers of Eastern European migrants who would come to Britain after 2004 and put no transitional controls in place at all.

Greetings Will.

Interesting post, I’ve been seeing your posts pop up for quite a while now.

Given what you share, i thought you may enjoy what I do.

I share a look at obscure histories, the ones left out of mainstream interpretations.

Here’s my latest, continuing on in my recent series regarding Giants:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/a-historical-record-of-giants-2?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios