The Politics of Clarkson's Farm

From blokeish Top Gear Clarkson to Tory / Lib Dem 'Lovely Britain'

Clarkson’s Farm has recently been renewed for its fifth series, having become Amazon Prime’s most watched show ever in Britain. In May 2024, the month of season three’s release, it was streamed more than any other show, with 10 million viewers.

Others have written giving some of the reasons for the show’s success. Its characters fit various popular and familiar archetypes: the blundering but likeable lord of the manor (and fish out of water) Jeremy Clarkson, the apparently unsophisticated but in reality astute local boy Kaleb, the number-crunching, rule-obsessed killjoy Charlie, and the old man of the land Gerald. The characters battle together, and with each other, to overcome various challenges both natural (the vagaries of livestock, crops, and the weather) and human (West Oxfordshire District Council). All of this together with the rural setting provides a strong sense of groundedness and authenticity.

Clarkson’s Farm is also, importantly, almost completely English in an England that is rapidly becoming less so with every passing year. Most TV and advertising portrays this transformation as being even more drastic than it is in reality, and part of the appeal of Clarkson’s Farm is that its setting is one of genuine, deep continuity with historical England, not one of rupture or of astroturfed continuity like, say, Bridgerton.

The experience of watching the show when the adverts come on is quite arresting. Contemporary British advertising could be pretty accurately described as an excessively twee, accelerated and improbably constituted version of the great replacement. Implausible racial combinations and levels of representation, all overlaid with a somewhat cloying ‘have a nice cuppa tea’ faux-cosiness; watching a few of these and then being suddenly transported back to Clarkson’s Cotswolds farm is whiplash inducing.

From Top Gear Clarkson to Clarkson’s Farm Clarkson

Jeremy Clarkson has traditionally been pretty clearly identified with Tory Britain in its Thatcherite guise. Born and brought up near Doncaster to upwardly mobile parents he moved south, lost his accent and made his career in journalism based on cars and an un-PC blokeishness.

Yet like most British people (perhaps people in general) Clarkson is conservative but in a non-ideological, idiosyncratic and often sentimental way, representing the average person far more closely than more explicitly political right wingers do. I mean this more in his approach to political questions than in his actual opinions, though these too generally do not stray too far from the centre ground, even when he is representing the minority position.

He is pro free market and anti regulation, against PC, wokeness and left-wing activism, and valorises common sense and plain speaking. He was a soft Remainer for both emotional and practical reasons, as with the British public in general he wears his anti-Americanism with pride and has an emphatic distaste for Trump. He writes against the death penalty and expresses confusion about, but some sympathy for transgenderism. He mocks climate change but is concerned for the natural world.

In general he likes to shock but is also keen to be normal and to stay inside the Overton window of respectability, exemplified by his climbdown after his column expressing the desire for Meghan Markle to be given the Cersei Lannister treatment led to more outrage than even he was expecting.

Top Gear’s Clarkson was younger and due to the nature of a show travelling round the world and driving cars, he was freer too. Restrictions on his activities were an irritant but he could always just move on to the next location if they became too onerous.

Clarkson’s Farm’s Clarkson has come home and has become tied to a specific place: he has thus found himself restricted in innumerable and frustrating ways, both natural and artificial. He cannot control the weather, how his animals behave, the law or the decisions of local governments which hem him in; he cannot just up and leave but has to make things work the best he can where he is. This new iteration is much closer to the life experiences of ordinary people than the one of globetrotting motoring journalist was.

This Clarkson is also softer. In a role reversal from Top Gear Clarkson, many scenes have him playing the role of the somewhat effete liberal, displaying his ignorance of practical farming matters and blanching at realities like castrating lambs and porcine cannibalism. He also starts getting into some of the great enthusiasms of the British middle classes. He tries his hand at ‘wilding’ his land, creating a natural idyll out of previously farmed or waste areas. He develops a farm shop and restaurant to sell local produce and he converts part of the farm to regenerative agriculture to improve soil health and biodiversity.

Clarkson’s Farm as an intersection between Tory Britain and Lib Dem Britain

As one early review of Clarkson’s Farm noted, ‘Clarkson’s gone soft’. In some ways, he has even become a bit Lib Dem, in the sense that Lib Dems are Tories gone soft.

Here a distinction must be made between Lib Dems as a party and Lib Dems as voters. As ‘The Right mustn't give up on Yellow England’ points out, while Liberal Democrat policies are about as left wing as those of Labour, among voters a large part of the party’s appeal is that it is seen as an alternative to the Tories that is not left wing, or at least not as left wing as Labour is.

It was these Lib Dem-Tory switchers that drove the party’s wins in previously Tory seats at the last election. These voters are not particularly left wing: in Onward’s post election report for example, Tory-Lib Dem switchers cite reducing immigration as the top thing the Tories could do to win back their vote, with 53% of them wanting immigration to be cut a lot and 22% cut a little.

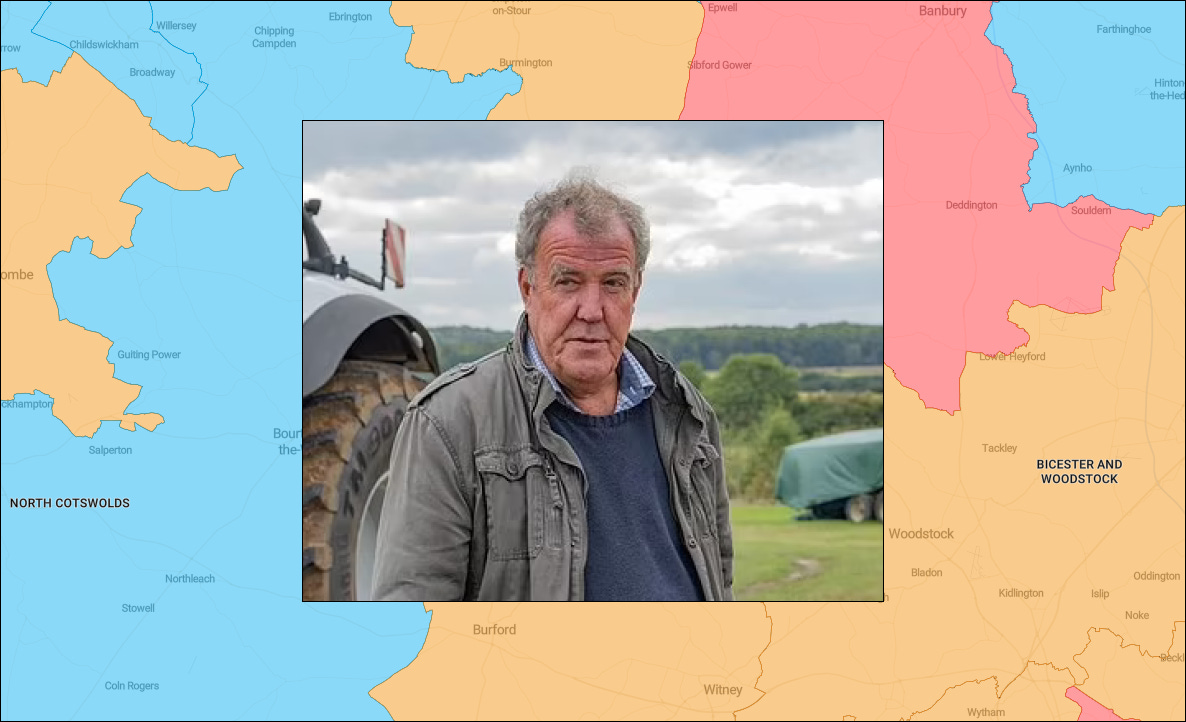

Clarkson’s Farm’s physical location fits this intersection: situated as it is in West Oxfordshire, part of what has been termed ‘lovely Britain’ by the Economist. While technically just inside the constituency of Banbury, which switched to Labour for the first time this election (due to most of the constituency’s population living in Banbury the town), it is surrounded by a patchwork of Tory and Lib Dem constituencies which were all Tory in 2019. This location is where Lib Dem (or Lib Dem curious) Britain merges into Tory Britain, the Severn-Wash line, or the point where the South meets the Midlands. There are a lot of Lib Dem constituencies just to the south of this line, and few above it.

This Clarkson of Clarkson’s Farm has a large and cross-cutting appeal, reaching beyond his traditionally blokeish right wing constituency to Tory / Lib Dem ‘lovely Britain’ types who prefer a somewhat more sensitive, bucolic brand of conservatism. Taken together this is a large group: it is no wonder that Dominic Cummings has reportedly been targeting Clarkson for his startup party.

Clarkson himself is quite politically astute, having recognised, despite his advocacy for Remain, that the political class can become so out of touch with public opinion that they can be taken unawares by political events: Brexit in 2016 and, he posits, mass immigration now. There are currently incipient rumblings about Clarkson as a political figure: Clarkson’s Farm has given him an unlikely role as a spokesman for British farmers and he is due to speak at the protest in London against the inheritance tax changes on the 19th of November. I could easily see him being able to develop this into something more if he is willing to give up his current comfortable position.

I was thinking about jarring adverts listening to the Rest is History recently. Lots of overly enthusiastic yoof jabbering or Serious Northern Women - nothing aimed at the listener of the podcast.

I love the likening of contemporary tv adverts to the great replacement.